With Russia and the U.S., Nuclear Risks Never Go Out of Vogue

(Russia Matters – russiamatters.org – Jon B. Wolfsthal – November 8, 2018 – russiamatters.org/analysis/russia-and-us-nuclear-risks-never-go-out-vogue)

Jon B. Wolfsthal is the director of the Nuclear Crisis Group and a former senior director on the National Security Council.

This week marks an important nuclear milestone of the Cold War: Thirty-five years ago, the United States almost accidentally provoked the Soviet Union into starting a nuclear war for fear that the West was about to use its nuclear weapons first.  The Able Archer event of 1983 should serve as an important reminder that despite billions of dollars of investments in the most advanced machinery, technology and training, nuclear weapons have inherent risks that often escape the ability of even the most thoughtful and cautious officials to control or understand. Sadly, few outside of the nuclear priesthood know about the event and what it means for our future security. But as the United States, NATO and Russia go back to the Cold War habits of annual military exercises that include simulating escalation to nuclear weapons use, the 1983 event holds powerful lessons that we ignore at our own peril.

The Able Archer event of 1983 should serve as an important reminder that despite billions of dollars of investments in the most advanced machinery, technology and training, nuclear weapons have inherent risks that often escape the ability of even the most thoughtful and cautious officials to control or understand. Sadly, few outside of the nuclear priesthood know about the event and what it means for our future security. But as the United States, NATO and Russia go back to the Cold War habits of annual military exercises that include simulating escalation to nuclear weapons use, the 1983 event holds powerful lessons that we ignore at our own peril.

The Back Story

During the Cold War, large-scale military exercises by both NATO and the Soviet Union/Warsaw Pact countries were routine annual events. NATO’s war games, held every fall, were seen by the alliance as stabilizing, reassuring allies and needed to deter potential Soviet aggression. Throughout the 1960s and 1970s, NATO simulated repelling a Soviet attack and often ended exercises by going on the offensive with nuclear weapons to defeat what was expected to be an overwhelming Soviet conventional attack.

During the Cold War, large-scale military exercises by both NATO and the Soviet Union/Warsaw Pact countries were routine annual events. NATO’s war games, held every fall, were seen by the alliance as stabilizing, reassuring allies and needed to deter potential Soviet aggression. Throughout the 1960s and 1970s, NATO simulated repelling a Soviet attack and often ended exercises by going on the offensive with nuclear weapons to defeat what was expected to be an overwhelming Soviet conventional attack.

But in the early 1980s, without the West’s full understanding, things started to change inside the Soviet Union. Soviet leaders had begun to convince themselves that Moscow was falling hopelessly behind the West’s military might. Worse, they were increasingly sure that the United States was seeking conventional and nuclear superiority and might use it to undertake a nuclear first strike without warning. In fact, there was concern that such a strike “out of the blue” might come disguised as an annual NATO military exercise. The election of Ronald Reagan, the launch of the Strategic Defense Initiative to develop national missile defenses that could defeat any Soviet attack and the looming deployment of short-flight-time Pershing II ballistic and stealthy ground-launched nuclear-tipped Tomahawk cruise missiles in Europe all combined to put Moscow on alert that a nuclear attack could come at any time.

To defend against this risk and to ensure that the Soviet Union would have advance warning of any such attack, Soviet spies and embassies were tasked in 1981 to be on special lookout for signs that the United States was preparing to use nuclear weapons. The idea, called Operation RYAN (the Russian acronym for “nuclear missile attack”), was to create a kind of human early-warning network to give Moscow time to prepare and, if needed, launch a pre-emptive nuclear strike. In the days before social media, such signals could be slow, but they supplemented Russian national technical means that also lagged far behind those of the West.

NATO’s 1983 annual fall military exercises culminated with Able Archer, a command exercise simulating the release of conventional and nuclear weapons. But this routine war game troubled the Kremlin, whose new human network picked up and reported that the activities might be associated with a U.S. decision to initiate nuclear war. In moves dismissed at the time by the West as propaganda, Moscow moved to load Warsaw Pact planes with nuclear weapons and put Soviet SS-20 nuclear-tipped intermediate-range missiles within range of western Europe on high alert. It was not known until several years later, after the defection of a senior Soviet spy from London, that the NATO exercise was seen as anything but routine and fed into fears of a NATO nuclear first strike that could have touched off a full-blown nuclear exchange between the United States and the Soviet Union.

The Able Archer event, once the full scope became known to the United States and its European allies, marked a turning point in the Cold War. As much as anything else, it led to efforts by then President Ronald Reagan and Mikhail Gorbachev to reduce the nuclear danger and pursue broader reductions and disarmament. In particular, the fear that misunderstandings could drive leaders on either side to make rash nuclear decisions for fear that decision time was short led to the negotiation of the 1987 Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces Treaty, an agreement now on the chopping block. The treaty banned all ground-based missiles with ranges from 500 to 5,500 kilometers, systems with short flight times that put leaders in Europe and Moscow on edge because they could reach their targets—including leadership and command and control—in 15 minutes or less.

Of course, there is much more contact and exchange between U.S. and Russian officials today than during the Cold War. The chances of missing such a massive mismatch between actions and intentions are smaller now. And yet, the United States and Russia are in the longest period without a serious sustained high-level dialogue on strategic stability and nuclear issues since before the Cuban Missile Crisis. President Donald Trump has recently threatened to withdraw from the INF Treaty that helped increase decision time in Moscow and Washington and reduce the pressure on leaders in both countries to act precipitously. And there is now growing concern that the United States may either let New START expire in 2021 or move to kill it outright to prevent its extension by a future administration. While the United States has no immediate plans to deploy a new sea-launched cruise missile with nuclear weapons in Europe, the Trump administration is interested in such a weapon-a move that could further exacerbate crisis instability with Russia.

The Lessons

As with many historical events, Able Archer leaves room for interpretation and further research. But in today’s increasingly tense climate, it offers obvious lessons for those now responsible for preventing nuclear conflicts and strategic misunderstandings.

The first is that there are risks associated with nuclear weapons that cannot be completely eliminated. Human actions, perceptions and the complexity of existing weapons systems always carry the chances for error. Some embrace these risks and believe they help make nuclear weapons stabilizing. Others believe that underestimating the nuclear danger is a recipe for our global extinction. But no one should believe that we have perfect control over such weapons and the people who make decisions behind their possible use.

The second is that for deterrence to work efficiently, both sides in a deterrent construct must understand the intentions of the other and correctly express what actions are to be deterred. Officials can and have argued over whether ambiguity in deterrent relationships is good or bad, but a certain amount of clarity is a prerequisite. Such clarity requires contact and communication between both the military and political leadership. Chairman of the Joint Chiefs Gen. Joseph Dunford has been in somewhat routine contact with his Russian counterpart, Gen. Valery Gerasimov, over issues related to Syria, but there is no ongoing military-to-military or high-level civilian nuclear dialogue or negotiation underway. The strategic stability talks between the U.S. and Russia-proposed under President Barack Obama-have been held only once, under the current administration, and have been largely moribund since mid-2017, often held hostage to other issues and controversies. Adequate communication is lacking in both the U.S.-Russia and the U.S.-Chinese relationships today and that increases the risk of miscommunication and unintended conflict.

Lastly, as we now know, despite the best intentions and efforts by the United States intelligence community, in the early 1980s Washington missed obvious signs that Moscow was both convinced of its own weakness and paranoid about U.S. intentions. What the White House and Pentagon saw as routine and reasonable actions to reassure our alliance partners and to signal resolve to our adversaries were seen by the Soviets not only as threatening but as actual preludes to an attack. Evidence of this was dismissed by the greatest Sovietologists of the day, and so the signs failed to influence policy. This is not that different from today’s dynamic in which President Vladimir Putin’s routine complaints about missile defenses and NATO enlargement are seen not as legitimate causes for concern but as rhetorical propaganda designed to undermine NATO’s cohesion. The risk that such misunderstandings can spiral out of control seems especially great now that large-scale military exercises like Russia’s recently completed Zapad and NATO’s ongoing Trident Juncture in Norway have once again become regular events on both sides.

Many in the United States, especially those pushing for new, more usable nuclear weapons, are convinced that Russia is pursuing a more aggressive nuclear policy to dominate its “near abroad” and threaten the NATO alliance. Others are increasingly convinced that Russia’s growing reliance on nuclear weapons is more a sign that it perceives itself as weak than a sign of its advancing strength. American decision makers are once again failing to consider alternatives and risk falling victim to group think. The inability or refusal to pursue sustained high-level and principled engagement with Russian leaders to better communicate and understand each other ignores the precise lessons we should draw from Able Archer and risks once again putting America and our allies at unnecessary risk of a nuclear conflict no one wants or even anticipates.

Article also appeared at russiamatters.org/analysis/russia-and-us-nuclear-risks-never-go-out-vogue with different images, bearing the notice: “© Russia Matters 2018 … This project has been made possible with support from Carnegie Corporation of New York,” with a footer heading entitled “Republication Guidelines” linking to: russiamatters.org/node/7406, which bears the notice, in part:

“If you would like to reprint one of these articles, a blog post written by RM staff, one of our infographics or a fact-check, we ask that you follow these guidelines:

- Include a prominent attribution to Russia Matters as the source and link back to the original at RussiaMatters.org.

- Retain the hyperlinks used in the original content.

- Do not change the meaning of the article in any way.

- Get an ok from us for non-substantive changes like partial reprints or headline rewrites and inform readers of any such modifications (e.g., This article first appeared on the Russia Matters website with the headline “Russian Election Interference in Trump’s Own Words”).

- Let us know about the reprint and send a link!

Please note that Russia Matters cannot grant permissions for third-party content, including articles, photographs and other materials not produced by our team.

Questions? Email us at RussiaMatters@hks.harvard.edu.”

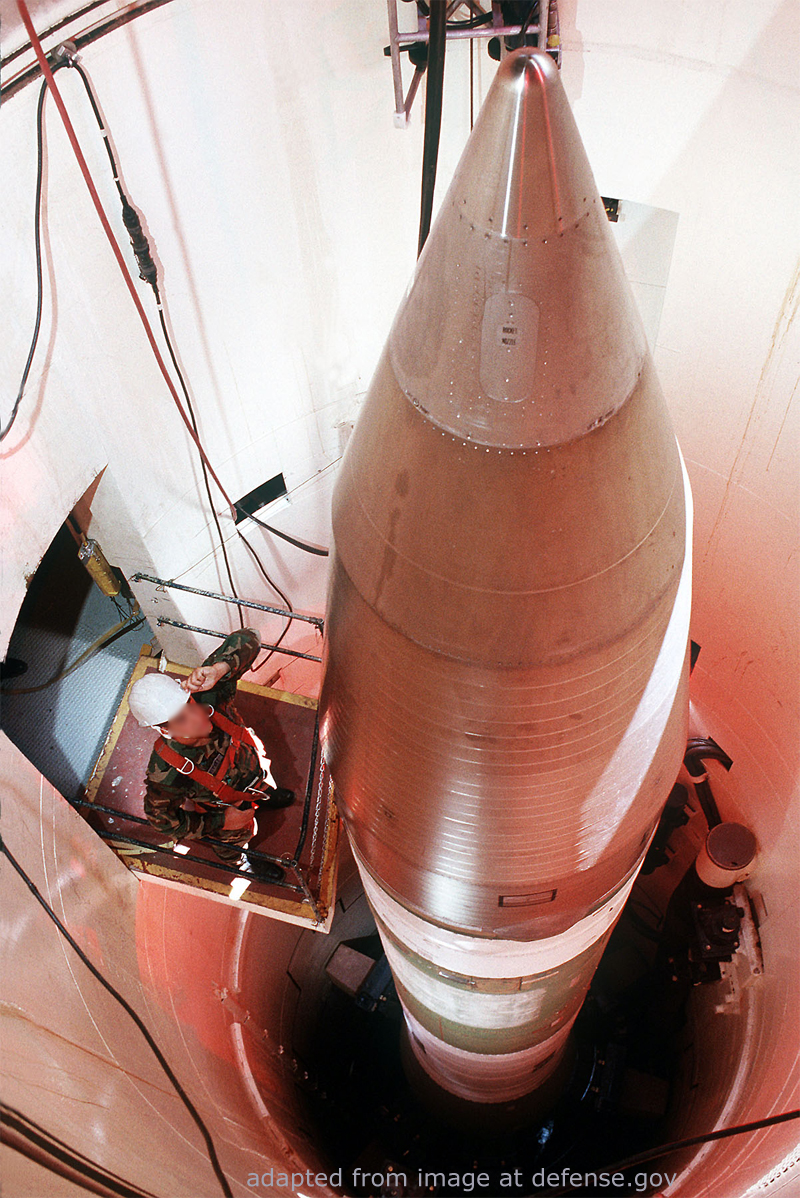

[featured images are file photos]