What Led to Putin’s Blunder in Ukraine?

(Russia Matters – russiamatters.org – Simon Saradzhyan – Feb. 24, 2023)

Simon Saradzhyan is the founding director of Russia Matters.

- First, Putin was motivated by his perception that there were acute growing threats to several of Russia’s vital national interests as he saw them, including the interest in preventing Ukraine’s “escape” to a hostile hegemon’s camp.

- Second, Putin may have believed he had run out of non-military options for responding to these threats.

- Third, Putin thought he had a reasonable hope that his war would succeed in warding off the aforementioned threats.

The jury might still be out on whether Putin really thought he had run out of non-military options of dealing with the perceived threats to Russia’s vital interests, but it is increasingly clear that he seriously overestimated (1) the chances that a full-blown invasion could succeed in warding off these threats and (2) the sum of net costs that such an invasion would impose on Russia. It is perhaps this misguided war optimism that played the most decisive role in shaping Putin’s erroneous decision to choose the full-scale invasion as a means of re-anchoring Ukraine to Russia and preventing NATO’s further expansion along Russia’s borders.

That Putin chose the full-blown invasion option in spite of a wealth of publicly available evidence that it wouldn’t be a walk in the park constitutes an important lesson for those of us seeking to anticipate the Russian dictator’s choices: Rather than assume that Putin would choose the policy option “common sense” would indicate, one should try to grasp what costs and benefits the dictator associates with each policy option available to him and, more importantly, what value he assigns to each of the pros and cons, no matter how misinformed his perceptions might be.

The Growing Threat of Ukraine’s ‘Escape’ to the West

When announcing his “spetsialnya voyennaya operatsia” (SVO) against Ukraine on Feb. 24, 2022, Putin asserted that its goals would be to defend the population in separatist-controlled parts of Donbas from “genocide” as well as to demilitarize and “denazify” Ukraine as a whole. In reality, however, the scale of the Russian offensives, which were simultaneously launched from the north, south and east, indicated that the strategic aim of the SVO were much grander than its stated aims. It was to subjugate Ukraine, robbing it of any substantive agency on foreign, defense and other policies in ways that would advance Russia’s vital interests as seen by Putin, such as preventing the arrival of hostile powers or regional hegemonies on Russian borders; ensuring Russia is surrounded by friendly states, among which Russia can play a lead role and in cooperation with which it can thrive; ensuring the survival of Russia’s clients; and re-gaining unhindered access to Ukrainian markets and labor force (X1 in Table 1, Table 2).

Some would argue that the February 2022 invasion was merely a continuation of the one that began in 2014. But I believe it constitutes a new intervention, separated from the earlier aggression by significant lulls in fighting when the rate of battle-related deaths in Ukraine was lower than Ukraine’s rate of murders or traffic deaths. Though fighting in the east never died down completely, major clashes there had pretty much ceased by 2017. This de-escalation came as the team of Ukraine’s then president Petro Poroshenko became convinced that their country’s armed forces at the time were too weak either to dislodge Russia and its clients from the already occupied territories or to prevent more landgrabs should they be attempted. At the same time, Putin and his team were still hopeful that the so-called Minsk-2 agreement would eventually be implemented on terms that would keep Ukraine in Russia’s orbit, advancing the aforementioned Russian vital interests. The agreement, which was co-signed by representatives of Russia, Ukraine, the separatists and the OSCE on Feb. 12, 2015, provided for Ukraine not only to grant the separatists amnesty but to “hold direct dialogue” with them on “modalities of local elections,” on adopting “laws on self-government in separatist-controlled parts of Donbas and on the special status of these parts” and also to “carry out constitutional reform in Ukraine … providing for decentralization as a key element.”

The Kremlin continued to pin its hopes on Minsk-2 even when Poroshenko lost to Volodymyr Zelensky in Ukraine’s April 2019 presidential elections. These hopes were not unfounded. After all, Zelensky had campaigned on promises to resolve the Donbas conflict peacefully, so the Kremlin had grounds to think the young new leader would prove more willing to implement the deal than his predecessor. As time went on, however, Moscow grew increasingly confident that Zelensky would not implement Minsk-2 in ways that would advance Russia’s aforementioned vital interests, giving Moscow’s allies in Ukraine a de facto veto over Kyiv’s geopolitical re-orientation. Initially, Zelensky and his team did make an effort to advance the implementation of Minsk-2, even though these efforts were not exactly welcomed by the radical ultranationalist forces in Ukraine itself. Eventually, however, Zelensky and members of his team began to send signals that the agreement could not be implemented as it was and that it required “re-thinking,” while also blaming Russia for the stalemate. In Putin’s eyes, such intransigence reduced the menu of non-violent options available to him for keeping the West out of Ukraine in forms he found unacceptable (X6 in Table 1).

Having failed to obtain guarantees of Ukraine’s neutrality from Kyiv, Putin made one last attempt to obtain them from the West. The fall of 2021 saw Russia send two ultimatum-like “proposals” to the U.S. and its allies—a draft treaty on security guarantees between Russia and the U.S. and an agreement on ensuring the security of Russia and NATO members. In them, Putin made three main demands: (1) that there be no more NATO expansion eastward, especially to Ukraine and Georgia; (2) that NATO withdraw military infrastructure placed in Eastern Europe after 1997; and (3) that the U.S./NATO deploy no strike systems in Europe capable of striking targets in Russia, such as intermediate- and short-range missiles. While there was some discussion in the West about the feasibility of some mutual pledges on the first and third points, the second was clearly a non-starter and it is difficult to see how Putin could have hoped for its implementation. It is, however, less difficult to see how Putin might have concluded that he had exhausted his non-forceful options after it became clear in January 2022 that the U.S. and its allies were not going to sign either of the treaties. In fact, Putin and his allies repeatedly claimed that if he were to continue to sit on his hands, Ukraine would have made the first move itself, launching an offensive to try to retake the separatist-controlled parts of Donbas. Putin and his aides claimed to possess evidence to back their claims, but have not produced it, and the Ukrainian authorities repeatedly denied preparing for an attack on Donbas.

That said, the Ukrainian armed forces did not sit idly by between the two Russian interventions.

Described as “impotent” in the spring of 2014 as it suffered one defeat after another, the Ukrainian army eventually began to gain strength. From 2013 through 2020, Ukraine’s military budget had nearly doubled, growing from 3% of Russia’s to 11%. The same period saw the personnel strength of Ukraine’s armed forces, measured as a share of Russia’s, increase from 15% to 23% (see Table 3). The country was able to procure more weapons and also received relatively advanced military equipment from the U.S. and its allies. In FY2020 alone, the U.S. provided $115 million through the Foreign Military Financing program and another $256.7 million through its Ukraine Security Assistance Initiative. U.S.-supplied systems included counter-artillery radars, patrol boats, electronic warfare detection and secure communications, satellite imagery and analysis capability and counter-unmanned aerial systems. Not only were the Ukrainian armed forces becoming larger and better armed, but they were also becoming better trained—thanks, to a significant extent, to participation in multiple programs and exercises for NATO partners. A Wall Street Journal article analyzing “the secret of Ukraine’s military success” last April calculated that NATO members had held “classes, drills and exercises involving at least 10,000 troops annually for more than eight years,” helping Ukraine “shift from rigid Soviet-style command structures to Western standards where soldiers are taught to think on the move.”

Failing to Assess the Net Costs of a Full-Scale Invasion

As stated above, the improvements in Ukraine’s military capabilities clearly did not escape Moscow’s attention, making the Kremlin wonder how much longer the Russian war machine could continue to serve as a convincing deterrent to Kyiv’s aspirations to integrate into the West. But if Russia were to use force to derail Ukraine’s aspirations, could Putin have had a reasonable hope2 in early 2022 of attaining his goal—to neutralize what he saw as a real threat to Russia’s national security emanating from Ukraine and its relations with the West—by such means? Did he believe he could attain the sought-after benefits, such as preventing deeper Ukraine-NATO integration, and that they would outweigh the costs for Russia, on and off the battlefield (X5 in Table 1)? As important, could the use of force have been limited to ensure that costs did not exceed benefits while still preventing NATO’s expansion deeper into Ukraine?

Calculations I did in 2021 suggested that a Russian leader who had access to open sources and the will to consult them was likely to conclude that there was a significant possibility that a full-blown conventional assault on Ukraine—meant to grant Russia sufficient leverage vis-à-vis Ukraine to prevent its escape to the West—could generate significant net costs and, therefore, it was unlikely that Putin would choose that option. The reasons I thought so at the time were as follows:

- For Russian units to succeed in a strategic offensive, the ground forces’ quantitative superiority over the Ukrainian military would have to be 3:1 at a minimum, per a popular rule of thumb, which was already no longer the case by 2020. In fact, that year the ratio was closer to 2:1 (see Table 3). As important, significant parts of the Ukrainian armed forces had been extensively trained by NATO instructors in the preceding several years and equipped with relatively advanced Western arms that would make combat more difficult for the attacking Russian forces.

- Russian troops could have expected an enduring insurgency in the Ukrainian regions north of Crimea and west of Donbas where anti-Russian sentiment had been running strong.

- If the “restoration of Russia’s dominion” over Ukraine entailed not just occupying lands east of the Dnipro (plus the western part of Kyiv across the river) but also incorporating them into the Russian Federation, then Moscow would incur significant financial costs (up to $64.5 billion a year by my count).

- Russia’s taking of left-bank Ukraine would lead to the re-freezing of Russia’s relations with the West, with qualitatively tougher sanctions.

- Whatever parts of Ukraine were left unoccupied, the government of this “rump” state could choose to redouble rather than abandon efforts at integration into Western clubs.

- Such an occupation would also alienate many pro-Russian voters in Ukraine and may make it difficult for those who remain pro-Russian to vote in areas outside Moscow’s control.

- The incorporation of Ukrainian lands east of the Dnipro would ultimately leave Russia without a buffer zone between itself and NATO, transforming a feared possibility into a stark reality.

Despite these probable downsides, most of which had been predicted by multiple experts writing publicly, Putin chose to intervene on a large scale. The reason for this misguided choice, in my view, is Putin’s failure to assess the net costs that such an intervention would entail. One reason for Putin’s futile hope that the net costs of the SVO would not be great was the misleading information he had been fed by formal and informal advisors, who had assured Putin that Russian troops would encounter little resistance. These advisors included senior officials from the Federal Security Service (FSB), which seems to have either misinterpreted or inaccurately conveyed the results of polls conducted in Ukraine, claiming that civilians would welcome Russian soldiers. Among these men was Gen. Sergei Beseda, who reportedly oversaw Ukraine at the agency, and FSB director Alexander Bortnikov. Also in the inner circle was Bortnikov’s predecessor and current secretary of the presidential Security Council Nikolai Patrushev, who claimed some three months before the invasion that the Russian army has come to rival that of the U.S. on Putin’s watch. The advisors also included Ukrainian oligarch Viktor Medvedchuk, whose daughter is Putin’s goddaughter. Medvedchuk, for instance, reportedly assured Putin that “Ukrainians saw themselves as Russian” and would greet the invading soldiers “with flowers.” Such propositions aligned with Putin’s own view of Russians and Ukrainians being “one people,” as he famously wrote in July 2021. In contrast to Medvedchuk’s unfounded optimism, “dissenting voices,” Russia’s foreign intelligence agency and Russia’s general staff raised doubts ahead of the invasion, according to FT’s sources.

The upbeat forecasts Putin received must have also aligned in his mind with recollections of how easy it had been to seize Crimea in the spring of 2014—an operation he had ordered despite his military and intelligence chiefs’ warnings not to. Putin—whose KGB recruiters identified him as having a “lowered sense of danger”—may have also taken heart from his relatively successful interventions in Georgia in 2008 and Syria in 2015.

Facing the Bitter Truth

That the 2022 campaign in Ukraine would prove to be nowhere as easy as the walk in the Crimean park of 2014 or Putin’s earlier military interventions became clear within days of the February 2022 invasion. The Ukrainians were tougher “than I was told,” Putin reportedly admitted to Israel’s Prime Minister Naftali Bennett, who visited Russia in early March. “This will probably be much more difficult than we thought,” Putin also told Bennett, implicitly acknowledging that he had miscalculated at least some of the costs of re-intervening in Ukraine on such a large scale.

In addition to the not-so-warm welcome by Ukrainians, the Russian invasion failed to achieve its initial objective of occupying left-bank Ukraine and Kyiv because of poor performance by Russian forces in general and the top brass in particular. Having come close to Kyiv in March, Russian troops spent much of the summer and fall in on-and-off retreats. A February 2023 report by the Belfer Center’s Graham Allison and Kate Davidson estimates that 130,000 Russian servicemen had been killed or severely wounded, that Russia had lost almost 5,000 tanks and other armored vehicles; and had ceded control over 57% of the territories it had captured since Feb. 24, 2022.

While we have no way of knowing for sure, it is unlikely that Putin and his generals expected such staggering setbacks. If they had, they would not have told members of the invading formations to pack their dress uniforms. That even some prime Western experts on the Russian military—who are arguably less susceptible to Potemkin narratives plied by some of Russia’s less scrupulous commanders—overestimated the capabilities of Russia’s war machine reaffirms the likelihood that Putin himself suffered from excessive optimism. They were not alone. Two days before the invasion, U.S. Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff Gen. Mark Milley gave visiting Ukrainian Foreign Minister Dmytro Kuleba a “you’re going to die” speech. “They’re going to roll into Kyiv in a few days,” Milley told Kuleba, according to The New York Times.

Further evidence that Putin expected far more of his top brass lies in the fact that, as of early 2023, Putin was already on his fourth commander for the “special military operation.”3

Surprisingly subpar performance has been observed not only among Russia’s top brass but at lower levels in the chain of command as well. One prime example was Ukraine’s deadly New Year’s Eve strike on a building housing Russian servicemen in the occupied eastern town of Makiivka using a U.S.-supplied HIMARS launcher.4 Ukrainian electronic surveillance units had apparently detected the site because the soldiers were using their cell phones—a long banned practice specifically meant to prevent detection by the adversary. The Russian soldiers’ violation of the ban indicates their commanders’ failure to enforce even the most vital orders on a tactical level—all the more astounding given the Russians’ own history of detect-and-kill operations. Equally illustrative in terms of the quality of Russian command decisions were reports that the building in Makiivka housed ammunition along with soldiers, intensifying the strike’s destructive power. The news led former separatist commander Igor Girkin (Strelkov) to call Russian commanders “basically untrainable.”

In addition to the military costs, Putin’s new gamble in Ukraine has also created geopolitical costs for Russia that he could not possibly welcome. Not only has the war prompted existing NATO members to commit to an expansion of their military capabilities, but it has also prompted long-neutral Finland and Sweden to pursue membership in the alliance. If Putin sees NATO expansion as a primary threat to Russia’s national security, then these countries’ entry into the bloc would make the threat a reality. Sweden and Finland’s inclusion in NATO would bring all of Russia’s Baltic Sea neighbors into the alliance and would expand the land border Russia shares with NATO members by 1,340 kilometers. Moreover, it would take a missile fired from Finland only two minutes longer to reach Moscow than a missile launched from Ukraine’s Kharkiv. This cannot be the kind of development Putin had hoped for when launching his military operation: Explaining in June 2021 why Ukraine’s membership in NATO would amount to the crossing of a Russian red line, Putin said it was because the flight time of a NATO missile from Kharkiv to Moscow would total seven to 10 minutes. Aside from deep-freezing relations with NATO and causing the bloc to expand, Putin’s war has also led to a sharp deterioration of Moscow’s relations not only with the United States, but also with the European Union, which had been Russia’s main trading partner until the war. This, in turn, has made Moscow even more dependent on trade with Beijing than it had been, shifting more of its eggs into one basket. Even Moscow’s most powerful ally has had a hard time seeing how Putin’s gamble could pay off geopolitically: In the view of some Chinese officials, the invasion indicates that Putin has gone “crazy” and his country now stands to emerge from the war as a “minor power” that would be much more diminished economically and diplomatically on the world stage.

In addition to underestimating the invasion’s military and geopolitical costs, Putin and his team have failed to grasp the scale of the damage that the West’s response would do to Russia’s economic, financial and technological capabilities. One of Putin’s closest economic advisors, central bank chair Elvira Nabiullina was clearly caught off guard when the West froze nearly half of Russia’s $630 billion in hard-currency reserves. Otherwise, she would have converted more of these reserves into assets the West could not easily seize, such as renminbi and domestically stored gold. Russia’s Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov openly admitted being surprised by the sanctions’ intensity: “Their current scale, of course, is striking… I didn’t expect this sort of imagination from the West,” he said in March 2022, singling out the targeting of Russia’s central bank as something “no one could have predicted.” Western sanctions have also undermined the Kremlin’s hopes for economic growth, at least in the short-term. Prior to the war, the government had expected GDP to grow by 4% in 2022-2023; now, it is forecast to decline by about 2% in that period, according to the International Monetary Fund. Even if Russia were to add the full Gross Regional Product of the entire Ukrainian regions of Donetsk, Luhansk, Kherson and Zaporizhzhia, which its forces control only partially, that would have failed to compensate for the more than 2% decline of its GDP in 2022.5

The sanctions have also made a sizable hole in Russia’s federal budget as well, with a deficit equivalent to 2.3% of GDP in 2022; in contrast, prior to the invasion, the Russian government had forecast a budget surplus of 1% for 2022. Russian access to technologies has also been significantly restricted, with the production of passenger cars reduced by 60% and the country’s defense industry reportedly forced to cannibalize washing machines for Western-made semiconductors for use in missiles. In addition to their structural impact, Western sanctions have punished Putin’s relatives and allies, with Russian billionaires’ fortunes shrinking by $67 billion, a 20% drop that’s more than four times as large as the rest of those on the Bloomberg Billionaires Index.

Ordinary Russians have suffered as well. Real incomes in 2022 were about 10% lower than in 2013, according to Oleg Buklemishev, director of the Moscow-based Center for Economic Policy Studies. And the number of Russian workers is shrinking—something the Kremlin probably did not plan for either. About 800,000 people left Russia since the beginning of the invasion for economic or political reasons, according to the aforementioned Belfer Center report. Russia’s IT sector alone saw an estimated 100,000 or more specialists flee Russia after the invasion. These developments represent a tangible blow for a country that has struggled with depopulation and a lack of particular skilled workers for much of its post-Soviet history.

All these costs do not represent a coup de grace,6 but they do significantly constrain Russia’s geopolitical choices. As long as Russia is estranged from the West,7 it would be compelled to keep more of its eggs in China’s basket. This estrangement also hobbles Russia’s economic and technological development.

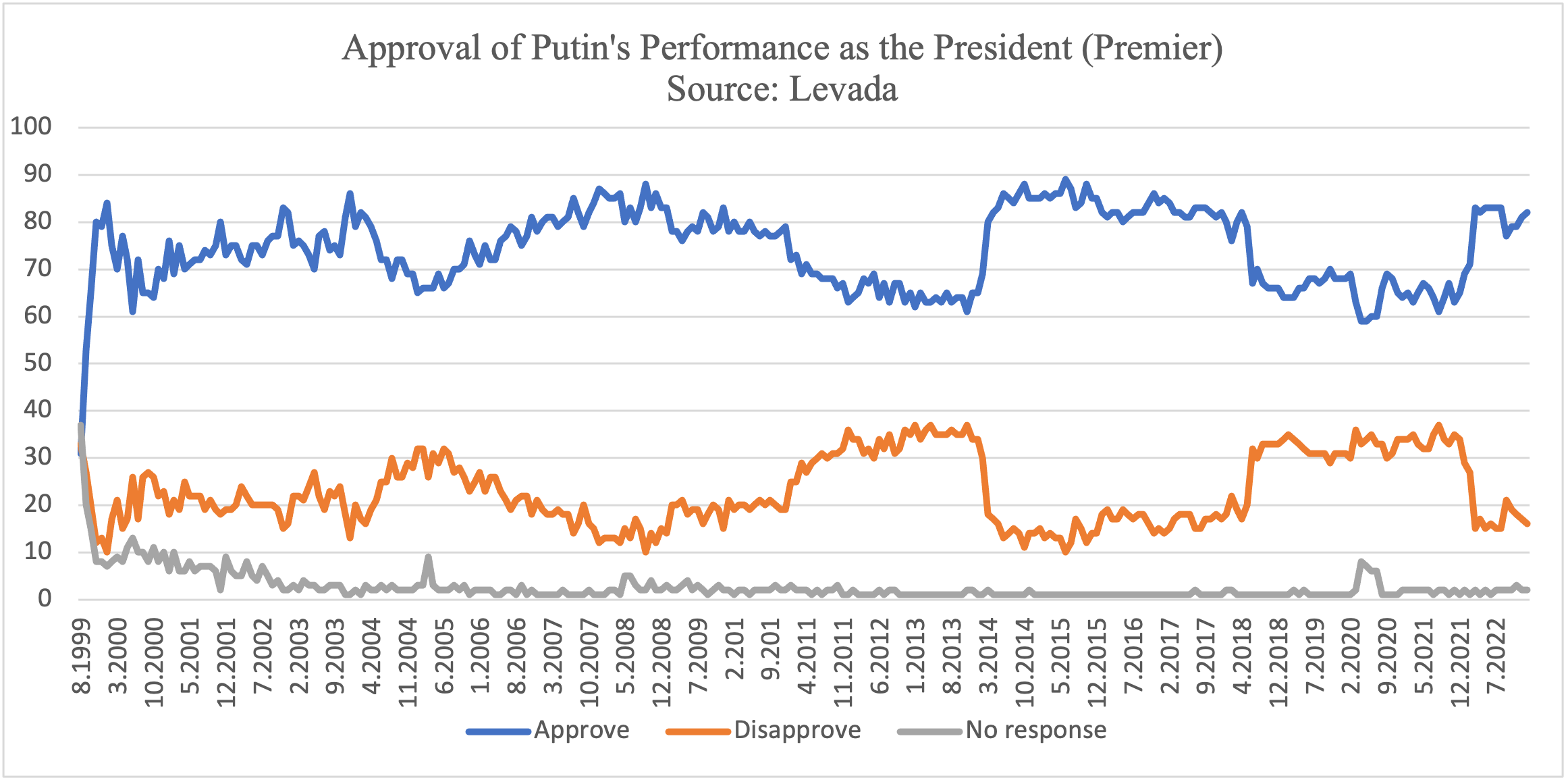

What Factors Likely Did Not Play a Role in Putin’s Decision to Invade

As stated at the outset of this paper, the author has inferred a number of other potential drivers of military interventions from the literature on the subject. For instance, a number of scholars have argued that a leader may launch a “small victorious war” for domestic political purposes, such as to boost his popularity.8 I agree that high popularity can serve as a primary source of legitimacy for autocrats (X3 in Table 1), but I don’t think Putin was in any urgent or strong need for a boost in his own popularity. Yes, his approval rating had dipped from its post-Crimea peak of nearly 90% in 2015, according to Russia’s Levada Center, but it had grown by 6% in the year preceding February 2022 (Figure 1). (Of course, pre-invasion saber-rattling likely contributed to that increase.) That year, his popularity averaged 65%, which meant he could be comfortably reelected if he wanted to hold early elections that year.

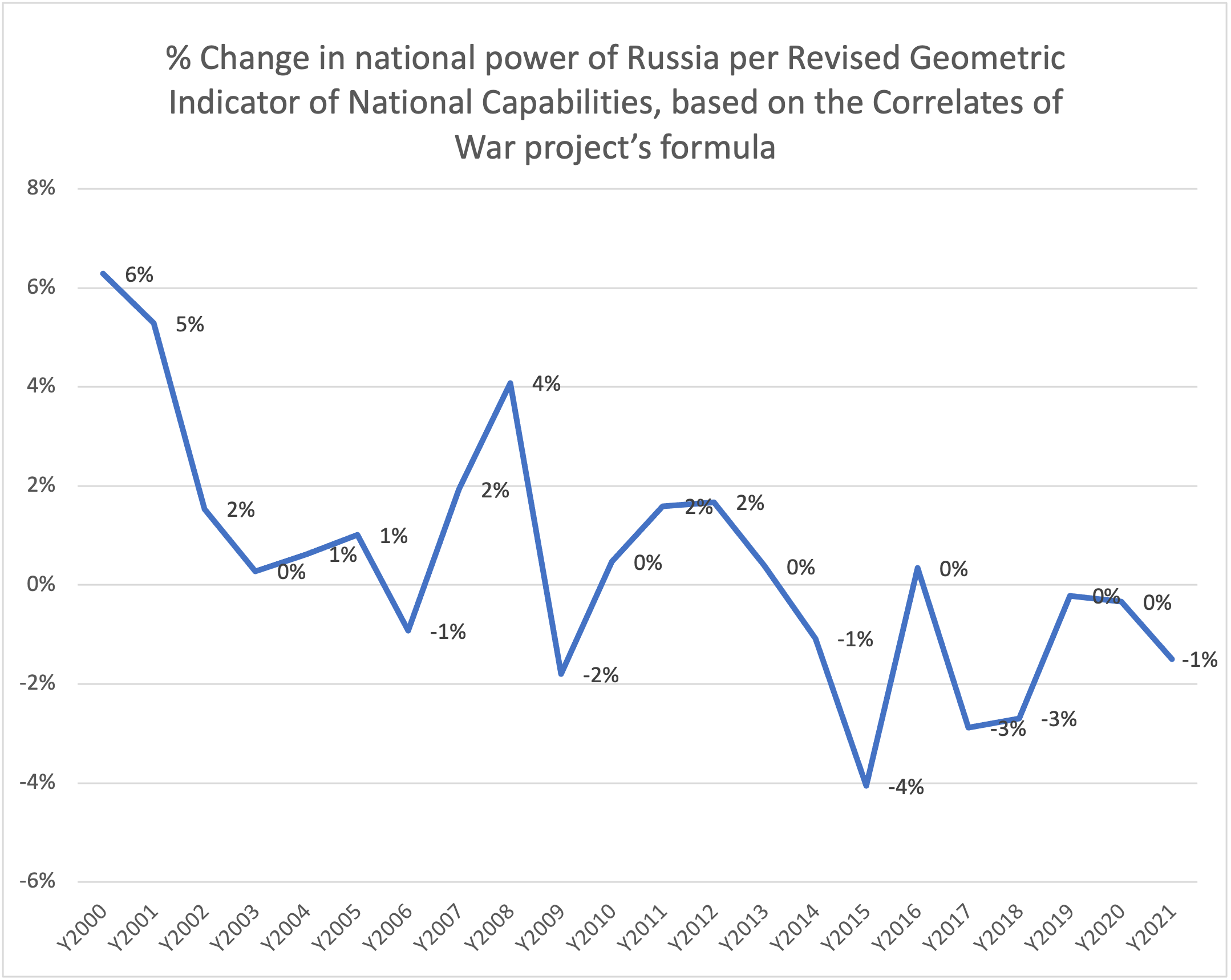

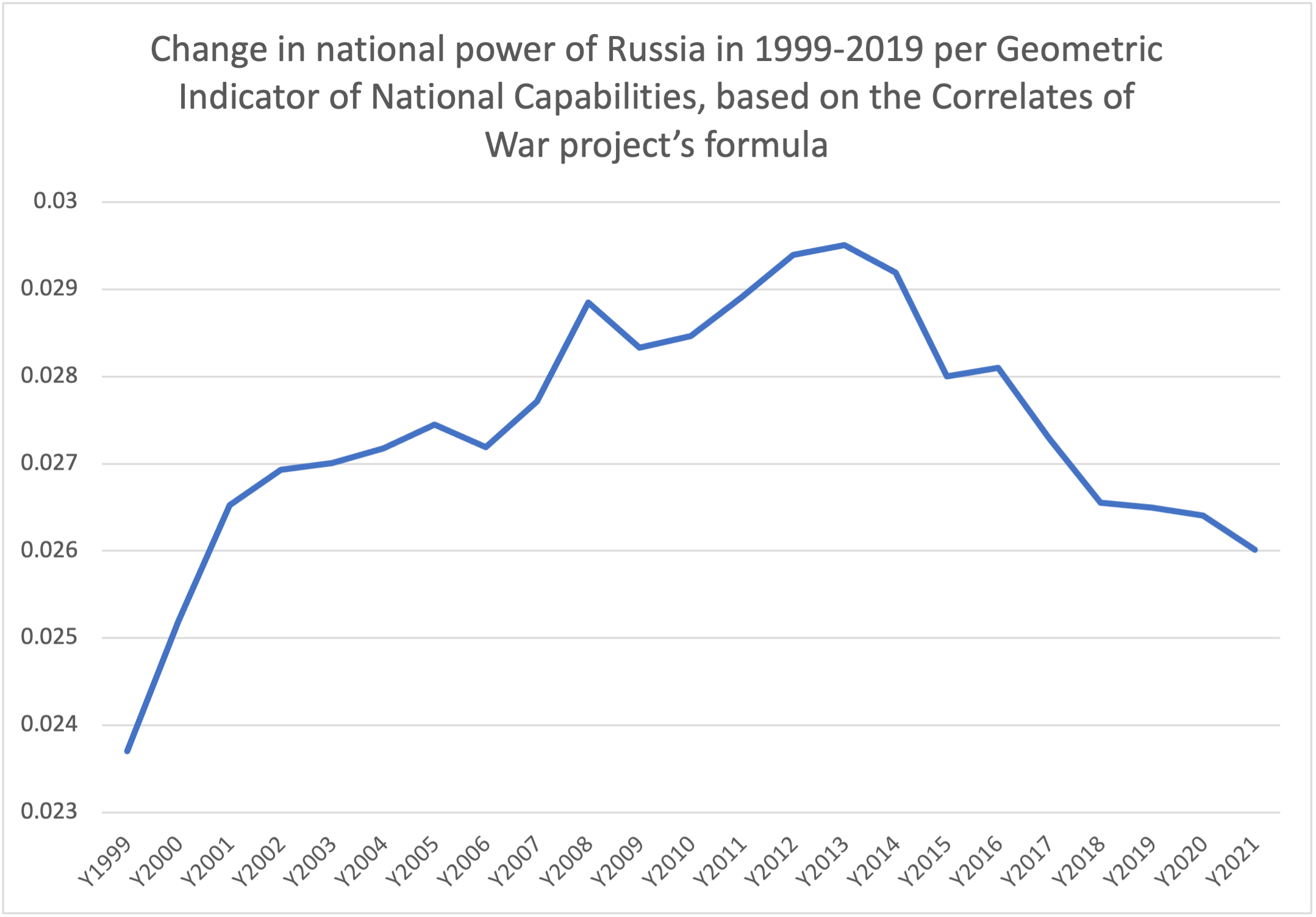

In addition to exploring whether a leader’s need for popularity can shape his decision to wage war against a foreign country, several scholars have argued that Russian leaders had in the past ordered interventions in part because they wanted to save face.9 However, I do not believe Putin faced any face-saving dilemmas concerning Ukraine in the early 2020s (X2 in Table 1). As long as separatist Donbas and annexed Crimea remained out of Kyiv’s control, as he had vowed they would, there was not much to save face about, in my view.10 Finally, several more scholars have posited that growth of Russia’s national wealth have made it more aggressive toward other states and more inclined to resort to military action.11 I have found no evidence of Russia’s national power increasing, however, in the period before the intervention. I have measured national power in the three preceding calendar years per a modification of the Correlates of War project’s formula for calculating national power. The calculation revealed that Russia’s national power did not change substantially in any of the three years preceding the year of invasion: 0% in 2022, 0% in 2020 and -1% in 2021 (see Figures 2 and 3).12

Looking Forward, Beyond ‘Common Sense’

As demonstrated above, a confluence of three factors was likely to have shaped Putin’s decision to intervene in Ukraine in 2022. First, Putin was motivated by his perception that there were acute growing threats to several of Russia’s vital national interests as he saw them, such as the interest in preventing Ukraine’s “escape” to a hostile hegemon’s camp. Second, Putin may have believed he had run out of non-military options for responding to these threats. Third, Putin may have calculated that there was a reasonable chance that his war would succeed in warding off the aforementioned threats. As this paper also demonstrated, Putin was wrong in his calculations thanks, in part, to poor intelligence and advice provided by his aides as well as his own analytical failures and his success with previous interventions.13

But Putin was not the only one who made a mistake in his calculations. In the months before his erroneous decision, multiple experts, including me, predicted he would not make such a mistake in the first place, given the net costs that a full-blown invasion would impose on Russia. And yet, Putin erred, and in a big way. That mistake doesn’t mean that Putin has gone “crazy” as the aforementioned Chinese official claimed. Rather, as a person who has known Putin since the 1990s observed in reference to his decision to reinvade Ukraine in 2022: “He’s not crazy and he’s not sick … he’s an absolute dictator who made a wrong decision—a smart dictator who made a wrong decision.” That, in spite of being rational, Putin did commit a blunder that can be described as strategic as it significantly constrains Russia’s geopolitical choices and hobbles its development, constitute a lesson to those seeking to anticipate this dictator’s choices. That lesson, as stated at the outset of this paper, is as follows: Rather than assume that Putin would choose the policy option “common sense” would indicate, one should try to grasp what costs and benefits the dictator associates with each policy option available to him and, more importantly, what value he assigns to each of the pros and cons, no matter how misinformed his perceptions might be.

| Case, as perceived by Putin | Intervention Y: (occurred or not) | X1: “Threat to vital national interests as seen by the leader.” (present or not) | X2: “Need for the leader to save face.” (present or not)

|

X3: “Need for the leader to ensure his popularity.” (present or not, measured by % change in Putin’s approval in the preceding year)

|

X4: “Color revolution in a country Russia is an ally of or which Russia seeks to make an ally.” (happening or not) | X5: “Leader’s reasonable hope that the intervention will succeed.” (present or not)

|

X6: “Leader has run out of non-military options for responding to crisis or such options were absent at the time of that crisis.” (yes or no) | X7: “Increase in national power in preceding calendar year, fueled by rising energy prices and/or other factors.” (present or not) |

| Georgia on verge of being granted MAP by NATO in 2008 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes

(-6%) |

No | Yes | Yes (because of Georgia’s assault on S. Ossetia) | Yes (7%) |

| Ukraine on verge of being granted MAP by NATO in 2008 | No14 | Yes | No | Yes

(-6%) |

No | No | No | Yes (7%) |

| Kyrgyzstan revolution of 2010 | No | No | Yes | No

(0.0%)

|

Yes | Yes | No | No

(-6%) |

| Syrian civil war of 2011 – present | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes

(-4 %) |

No | Yes | Yes | No

(-2%) |

| Ukrainian revolution of 2013-2014 | Yes | Yes | Yes | No

(0.0%) |

Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes (3%) |

| Belarus protests of 2020 | No | Yes | Yes | Yes

(-12%) |

Not yet | Yes | No | No

(-2%) |

| Conflict between Armenia and Azerbaijan in 2020-2022 | No | Yes | No

|

Yes

(-2%) |

No | Yes | No | No

(-2%) |

| Ukraine on verge of finalizing its escape to West from Russia’s zone of influence: 2022-present | Yes | Yes | No | No (+6%) | No | Yes | Yes | No (-1%) |

Table 2: Russia’s vital national interests as seen by the Russian leadership (in order of importance)15

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Table 3: Correlation of Russia’s and Ukraine’s military forces and resources

| Data from IISS’ Military Balance 2014 on Year 2013 | Russia | Ukraine | Ukraine’s as % of Russia’s | Data from IISS’ Military Balance on Year 2020 | Russia | Ukraine | Ukraine’s as % of Russia’s | |

| Military budget in billion USD, PPP | $81.4 | $2.4 | 3% | Military budget in billion USD | $40.7 | $4.3 | 11% | |

| Active military personnel, including | 845,000 | 129,950 | 15% | Active military personnel, including | 900,000 | 209,000 | 23% | |

| Army | 250,000 | 64,750 | 26% | Army | 280,000 | 145,000 | 52% | |

| Navy | 130,000 | 13,950 | 11% | Navy | 150,000 | 11,000 | 7% | |

| Aerospace Forces/Air Force | 150,000 | 45,250 | 30% | Aerospace Forces/Air Force | 165,000 | 45,000 | 27% | |

| Airborne | 35,000 | 6,000 | 17% | Airborne | 45,000 | 8,000 | 18% | |

| Reserve | 2,000,000 | 1,000,000 | 50% | Reserve | 2,000,000 | 900,000 | 45% |

Figure 2: Rate of change in Russia’s national power in 1999-2021, %16

Figure 2: Rate of change in Russia’s national power in 1999-2021, %16 Figure 3: Russia’s national power in 1999-202117

Figure 3: Russia’s national power in 1999-202117

Footnotes

- This paper’s approach toward inferring the potential drivers of Putin’s decision to re-intervene in Ukraine is based on the author’s earlier research. The fullest description of that methodology is available in the May 21, 2021, draft of his article, “When Does Vladimir Putin’s Russia Intervene Militarily and Why?” A shorter description of this approach is available at Saradzhyan, Simon, “When Does Putin’s Russia March Off to War?,” Orbis, Volume 66, Issue 1, 2022, Pages 35-57.

- This paper relies on the following definition of what constitutes a reasonable hope by John Patrick Day: “A’s hope that P is reasonable if and only if (1) P is probable in some degree, however, small; (2) the degree of A’s probability-estimate that P corresponds to the degree of probability that P; and (3) P is consistent both with itself and with the other objects A’s hopes.” John Patrick Day, “Hope.” American Philosophical Quarterly (1969): pp. 89-102.

- Putin fired three supreme commanders of this operation between Feb. 24, 2022, and Jan. 11, 2022. In that period, the average commander survived for less than 70 days in this post, if one counts Putin as the first commander, according to the author’s calculations. In comparison, the supreme commanders of Russia’s armed forces during its participation in World War I stayed an average of 161 days on the job, even though Russia underwent two regime changes in 1917 while fighting this war; commanders of U.S. forces during the Korean, Vietnam and second Iraq war survived 347, 983 and 448 days on the job, respectively.

- Kyiv claimed the strike had killed more than 400, while the Russian military initially admitted only 89 KIAs; independent open-source researchers as of Feb. 13, 2023, had identified 109 Russian servicemen killed at Makiivka.

- These four regions’ annual GRP totaled about $16.5 billion in 2020, which is the latest year that the Ukrainian government’s statistics agency had data for as of February 2022. That sum equaled about 1% of Russia’s 2020 GDP of $1,489 billion, as measured by the World Bank.

- Some Western experts have even resumed forecasting the imminent collapse of Putin’s regime or even Russia itself, like the Soviet Union in 1991. In my view, there are too many variables at play to make such prognoses. On one hand, Russia’s economy is much healthier than the Soviet Union’s was, and Putin has proved time and again that he is prepared to use force to defend his rule; on the other hand, autocratic regimes have been known to collapse with little warning.

- For this estrangement to diminish significantly, not only does Putin need to be succeeded by someone who is willing to normalize relations with members of the Western club, but key members of that club also need to find that successor acceptable to deal with.

- George Edwards, Samuel Kernell and John Benson have argued that leaders may intervene abroad to boost popularity at home. George C. Edwards, The Public Presidency: The Pursuit of Popular Support. New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1983; p. 26; Samuel Kernell, “Explaining Presidential Popularity.” American Political Science Review72, no. 2 (1978): pp. 506-522; John M. Benson, “The Polls: U.S. Military Intervention.” The Public Opinion Quarterly 46, no. 4 (1982): pp. 592-598.

- Jeremy R. Azrael, Benjamin S. Lambeth, Emil A. Payin, and Arkady A. Popov, “Chapter 12: Russian and American Intervention Policy in Comparative Perspective,” in eds. Azrael, Jeremy R., and Emil A. Payin, US and Russian Policymaking with Respect to the Use of Force. RAND Corporation, 1996.

- This factor is not discussed in the paper as there was no real threat of any kind of internal revolution in Ukraine in 2022.

- Cullen S. Hendrix, “Oil Prices and Interstate Conflict Behavior.” Peterson Institute for International Economics Working Article 14-3 (2014). Maria Snegovaya, “Think of Russia as an ordinary petrostate, not an extraordinary superpower,” The Washington Post, March 9, 2015, https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/monkey-cage/wp/2015/03/09/to-understand-russia-think-of-it-as-an-ordinary-petrostate-as-opposed-to-an-extraordinary-superpower/

- Simon Saradzhyan, and Nabi Abdullaev. “Measuring National Power: Is Putin’s Russia in Decline?.” Europe-Asia Studies (2020): 1-27. The Correlates of War project’s formula is also used to measure national capabilities in studies of military intervention such as Pickering, Jeffrey, and Emizet F. Kisangani. “Democracy and diversionary military intervention: Reassessing regime type and the diversionary hypothesis.” International Studies Quarterly 49, no. 1 (2005): 23-43; and Kaw, Marita. “Predicting Soviet military intervention.” Journal of Conflict Resolution 33, no. 3 (1989): 402-429.

- For one look at what Putin got right when calculating whether to invade Ukraine, see Walt, Stephen, “What Putin Got Right,” Foreign Policy, Feb. 15, 2023.

- The author chose the following criteria when deciding whether to include other potential counterfactuals in this table: either Putin himself stated publicly that he considered or would consider intervening, or it is known from open sources that a leader of a foreign country asked Putin for such an intervention.

- These interests were modified to reflect the impact of the Russian invasion into Ukraine in 2022.

- Formula available in Simon Saradzhyan and Nabi Abdullaev. “Measuring National Power: Is Putin’s Russia in Decline?.” Europe-Asia Studies (2020): 1-27.

- Formula available in Simon Saradzhyan and Nabi Abdullaev. “Measuring National Power: Is Putin’s Russia in Decline?.” Europe-Asia Studies (2020): 1-27.

Article also appeared at russiamatters.org/analysis/what-led-putins-blunder-ukraine, with different images, bearing the notice: “© Russia Matters 2018 … This project has been made possible with support from Carnegie Corporation of New York,” with a footer heading entitled “Republication Guidelines” linking to: russiamatters.org/node/7406, which bears the notice, in part:

“If you would like to reprint one of these articles, a blog post written by RM staff, one of our infographics or a fact-check, we ask that you follow these guidelines:

- Include a prominent attribution to Russia Matters as the source and link back to the original at RussiaMatters.org.

- Retain the hyperlinks used in the original content.

- Do not change the meaning of the article in any way.

- Get an ok from us for non-substantive changes like partial reprints or headline rewrites and inform readers of any such modifications (e.g., This article first appeared on the Russia Matters website with the headline “Russian Election Interference in Trump’s Own Words”).

- Let us know about the reprint and send a link!

Please note that Russia Matters cannot grant permissions for third-party content, including articles, photographs and other materials not produced by our team.

Questions? Email us at RussiaMatters@hks.harvard.edu.”