Stephen J. Cimbala: “Arms Control and the Trump-Putin Summit”

Subject: Arms Control and the Trump-Putin Summit

Date: Wed, 11 Jul 2018

From: STEPHEN CIMBALA <sjc2@psu.edu>

Arms Control and the Trump-Putin Summit

By Stephen J. Cimbala

Stephen J. Cimbala is Distinguished Professor of Political Science at Penn State Brandywine. Dr Cimbala is an award winning Penn State teacher and the author of numerous works in the fields of national security studies, nuclear arms control and other topics.

As US President Donald Trump prepared to meet Russian President Vladimir Putin at their summit on June 16, 2018 expectations ran high. A number of issues were candidates to appear on the agenda. Among these issues was the problem of maintaining nuclear-strategic stability as between the world’s two largest nuclear weapons states, the United States and Russia, and more broadly, among the rest of the international community.

As US President Donald Trump prepared to meet Russian President Vladimir Putin at their summit on June 16, 2018 expectations ran high. A number of issues were candidates to appear on the agenda. Among these issues was the problem of maintaining nuclear-strategic stability as between the world’s two largest nuclear weapons states, the United States and Russia, and more broadly, among the rest of the international community.

There can be no doubt that the past formula of strategic stability based on reciprocal nuclear deterrence, nuclear arms control and nonproliferation is under siege and faces an uncertain future. As political relations between NATO and Russia have deteriorated since 2014, so, too, has the extent of their ongoing commitment to nuclear arms control. To the contrary, the US and Russia accuse each other of having violated the Intermediate Nuclear Forces (INF) treaty, are engaged in a new wave of nuclear modernization, and have left the fate of the New START agreement in a state of limbo. In addition, the decision by  President Trump to withdraw United States support for the Iran nuclear agreement can only increase friction between Washington and the P-4 plus Germany who still adhere to the agreement.

President Trump to withdraw United States support for the Iran nuclear agreement can only increase friction between Washington and the P-4 plus Germany who still adhere to the agreement.

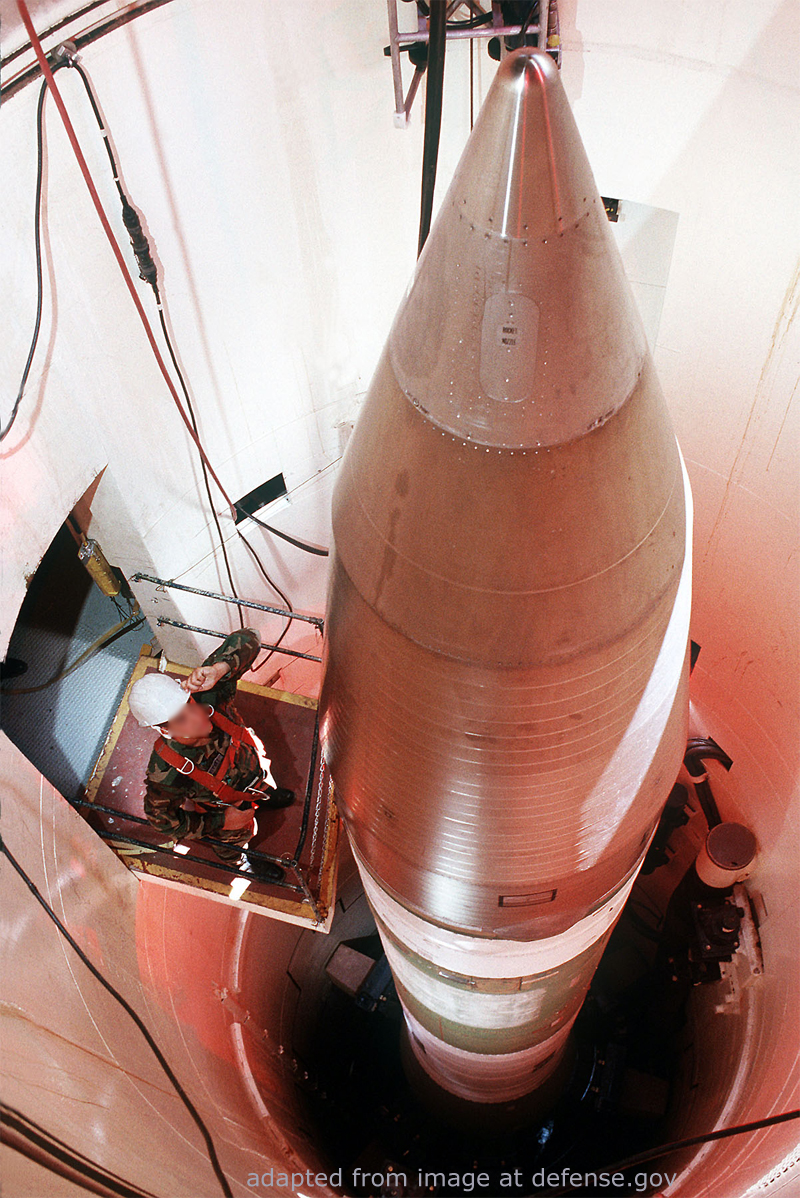

With respect to nuclear arms control, it would seem that the simplest and most straightforward thing for the US and Russia to do would be to implement the option for extending the New START treaty until 2026. Agreement on this point would at least temporarily cap the two states’ numbers of deployed and other  intercontinental nuclear launchers and warheads. However, even this basic step, as well as more ambitious arms control measures, will have to confront at least five “wormholes” that threaten to create enough uncertainty to defeat the most conscientious efforts by the US, Russia and others to limit or reduce the numbers and capabilities of nuclear weapons.

intercontinental nuclear launchers and warheads. However, even this basic step, as well as more ambitious arms control measures, will have to confront at least five “wormholes” that threaten to create enough uncertainty to defeat the most conscientious efforts by the US, Russia and others to limit or reduce the numbers and capabilities of nuclear weapons.

The first wormhole is the advent of hypersonic nuclear and conventional weapons. These weapons are moving rapidly from the imagination of military planners into working prototypes and deployable systems. As outlined in Putin’s dramatic address to the Russian Federal Assembly on March 1, 2018, hypersonic weapons might include: a nuclear powered and nuclear armed intercontinental cruise missile; hypersonic “boost glide” weapons, for example, Avangard re-entry vehicles launched from Sarmat intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBMs); and a new air-launched cruise missile (ALCM) capable of hypersonic speeds (Kinzhal). Presumably each of these systems would have the capability to maneuver in order to deceive antimissile and air defenses, since Putin’s rationale for the new weapons was the growing threat from US missile defenses (see below). The United States has also indicated interest in hypersonic weapons, and until 2013 was widely perceived as the world leader in this category. Since then, increased interest in hypersonics by Russia and China has been noted in expert commentaries and media reports.

The second wormhole that complicates future nuclear-strategic stability is the problem of missile defenses. Russia charges that US missile defenses represent a proximate threat to Russia’s nuclear deterrent, but the US argues that its missile defenses are deployed to intercept small attacks from rogue states or accidental launches. Russia’s reasoning on this point derives from debatable assumptions about US strategy. Russia fears not only the possibility of a US nuclear first strike, but also a decisive conventional attack on its main nuclear forces and command-control systems (with so-called conventional global precision strike or PGS weapons). This disarming US conventional attack would be undertaken in the expectation that US missile defenses might be good enough to absorb Russia’s degraded retaliation (presumably nuclear). As is often the situation with “worst case” military strategizing, this Russian version of a US strategy defies scientific credibility and social common sense. No US first strike, whether nuclear or conventional, would destroy enough Russian retaliatory power to allow for an “acceptable” Russian retaliation except by lunatic standards. However, another version of Russia’s concern is that US political leaders or their military advisors might believe their own science fiction and, during a crisis, feel more optimistic about a “successful” conventional first strike. Let us hope not.

The third wormhole challenging orthodox thinking about nuclear-strategic stability is the problem of cyberwar. This problem has at least two different aspects. First, cyber attacks on nuclear weapons systems and command-control might create vulnerabilities that could be exploited by an attacker. Second, cyberwar conducted immediately prior to the outbreak of a crisis, but also during it, could confuse decision makers with respect to their opponents’ actual capabilities and-or real intentions. In the fog of (cyber)war, the probability of mistaken decisions for preemption based on faulty assumptions or misinformation could increase significantly. This relates to one of the risks of hypersonic weapons. Weapons moving at Mach 5 to Mach 10 or greater will allow decision makers very little time to decide upon a response, compared to slower weapons. The combination, of leaders who were fearful of imminent cyber-confused command-control systems and of hypersonic attackers, would work against deterrence and nuclear crisis stability.

The fourth wormhole that increases the difficultly of maintaining or improving nuclear stability is the proliferation of nuclear weapons and the growth of civil nuclear power industries that create latent potentials for nuclear weaponization. The possibility of creating new nuclear weapons states in Asia and in the Middle East, with the potential for regional destabilization and the involvement of outside nuclear powers in local conflicts, poses a serious risk for world order. New nuclear weapons states and threshold nuclear powers will have to go through a steep learning curve on issues of nuclear deterrence, crisis stability and arms control in a very short time, compared to the decades of Cold War learning permitted to the Americans and Soviets. The possibility that new nuclear weapons states will try to “use” nuclear weapons in creative ways short of firing them (e.g., by playing nuclear mind games, supporting coercive diplomacy, or making threats to lose control of their own nuclear forces under certain circumstances) should be studied more carefully by existing nuclear powers.

The issue of nuclear first use is the fifth wormhole complicating the problem of maintaining nuclear-strategic stability. Nuclear first use is the term of art applied to a comparatively small and selective use of nuclear weapons, as opposed to a nuclear first strike, suggesting a massive and much more destructive (and decisive) blow by the attacker. The US 2018 Nuclear Posture Review called for development of a wider spectrum of low yield weapons for use on various launch platforms. One rationale for more low yield nuclear weapons was that the US should be able to respond to any Russian first use of tactical nuclear weapons in a symmetrical manner without being forced into an overreach at higher levels of destruction. The presumption is that the availability of “tailored” capabilities for tactical nuclear response would be more dissuasive to Russia or others who might try to engage in nuclear first use as a bargaining move. Russia, in turn, has indicated that it reserves the right, under certain drastic conditions of conventional war against Russia, to engage in nuclear first use for the purpose of military de-escalation. The Russian objective would be to warn against further pursuit of US or NATO escalation in order to open the door to negotiation and conflict termination.

Throughout the Cold War and subsequently, the question whether a broader spectrum of US nuclear response capabilities would increase deterrence credibility was hotly debated, mostly with reference to the deterrence of attack against NATO Europe. Very much depends on the assumed scenario at play. A wider spectrum of lower yield nuclear weapons might provide policy makers with additional “degrees of freedom” to manage a local outbreak of nuclear war and to prevent it from escalating into something worse. On the other hand, an initial use of nuclear weapons regardless of the size of their yields might signal to the opponent that preparations were imminent for something more drastic. The enormous symbolism of the first nuclear weapon fired in wartime since the destruction of Nagasaki should never be understated. In other words: each rung on the nuclear ladder of escalation has the potential to serve as a firebreak between levels of commitment and destruction; or, on the other hand, as a detonator of increased levels of violence. During the Cold War, US theorists and policy makers were more frequently willing to support a wider range of limited nuclear options than were their European counterparts. Current US nuclear modernization plans include not only the availability of more lower yield weapons, but also technical improvements in the accuracy and reliability of those weapons (for example, the US B61-12 with adjustable yields from five to 100 kilotons and a precision guidance system).

If the preceding list of challenges to the preservation of nuclear-strategic stability and world order appears daunting, what responses by leading nuclear weapons states and alliances might be appropriate?

First, the US and Russia should immediately agree to extend the New START treaty to 2026. New START provides for reasonable limits on deployments of American and Russian warheads and launchers and an inspection regime to support it. Along with this, Russia and the US should consider limitations on missile defenses capable of intercepting nuclear weapons of intercontinental range, excluding limits on theater or tactical antimissile systems because they are less destabilizing. Under such an approach, the first post-New START arms limitation agreement between the US and Russia would follow the pattern of the US-Soviet agreements in the early 1970s to limit both offensive and defensive deployments (START I and the ABM Treaty).

In addition to the extension of New START, Russia and the United States should agree to reboot and salvage the Intermediate Nuclear Forces (INF) treaty. Instead of volleying back and forth charges of noncompliance with the INF agreement, the two states should recommit to observance of this accord and to transparency with respect to suspect deployments by Russia or by NATO. Action on this point is urgent before INF expires due to malign neglect and reopens the door to entire new generations of INF-range deployments (ground launched ballistic or cruise missiles with ranges between 500 and 5,500 km).

Second, the United States, NATO and Russia should establish regular consultative mechanisms for expert panels of scientists, military officers, intelligence officers, and diplomats to exchange views and share expertise on issues related to nuclear security and strategic stability. Some additional life support should be provided to the NATO-Russia Council, among other institutions, for this purpose. Throughout the Cold War and even during some of its most dangerous days, Soviet diplomats, intelligence operatives and military officials met formally and informally with American and allied NATO counterparts. Thank goodness for that. Of course, this proposal will require rebooting of the decimated US diplomatic corps and restoring diplomacy and intelligence to their rightful places in the formulation and execution of strategy.

Third, and related to the second point, increased transparency is needed about states’ views with respect to emerging technologies that might threaten strategic stability and about their commitments to develop or deploy those technologies. For example, will the modernization of US or Russian missile defenses emphasize the use of boost-phase technologies and, if so, does this imply the deployment of space based interceptors as well as space based sensors? As another example, what are the Russian, American (and for that matter, the Chinese) views of antisatellite weapons (ASATs) and their potential deployment in space? Apparently the US, China and Russia anticipate the eventual deployment of satellites that can repair or refuel other satellites and collect space debris. However, these same repair-refuel satellites could have the capability to stalk and destroy another state’s satellites on short notice.

And, speaking of China, it is high time to engage Beijing in nuclear arms limitation talks, even if the talks are lacking in transparency compared to the historical success of US-Soviet and US-Russian nuclear arms reductions. Regular consultations among military and other experts from all three states could raise shared awareness about each state’s nuclear priorities and strategic thinking. For example: what is China’s view of US-supported missile defenses in Asia, and how does it compare to Russia’s view of US missile defenses in Europe? Or, what is Chinese strategic thinking about the role of hypersonic weapons in future Chinese military strategy?