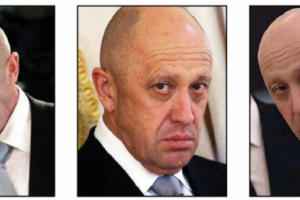

Prigozhin has captivated the West – but pundits have no idea what is going on

“Many Western pundits were quick to offer their hysterical takes on the weekend’s events in Russia”

(opendemocracy.net – Jeremy Morris – June 26, 2023)

Jeremy Morris is a researcher at Aarhus University, Denmark. His work covers labour relations, political economy, and the lived experience of people in Russia, Ukraine and other places since the collapse of the Soviet Union. He is the author of ‘Everyday Postsocialism’ (Palgrave, 2016). he writes sociologically about current events in Russia on his blog postsocialism.org.

The events of the last few days seem surreal, even by Russian standards.

Yevgeny Prigozhin, the huckster-cum-warlord, finally snapped after many complaints and accusations against the Russian Ministry of Defence. After what appeared to be a missile attack on his Wagner troops by Russian forces, Prigozhin made a grand appearance in Rostov – a hub and staging point for the Russian military. Wagner units then appeared to make a bold, rapid advance towards Moscow by way of another large Russian city, Voronezh. A number of Russian aircraft were shot down in the process, allegedly by Prigozhin’s forces. In Moscow and elsewhere, there were signs of hurried preparations by troops to repel an incursion.

This situation led to conflicting and hysterical reactions in the Anglophone war commentariat, a phenomenon going back to Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine that deserves serious sociological analysis. It’s not uncommon to come across Twitter accounts with hundreds of thousands of avid followers commenting with great confidence and seeming authority on every aspect of the war and in excruciating detail.

The scale of misplaced commentary from the pundit industry is such that, against my better judgement, I made a series of posts on Saturday bemoaning the irresponsible circulation of unverified information by mainstream journalists. I also, more out of luck than anything else, correctly assessed that the Prigozhin events did not constitute a ‘coup’. Instead, they were symptomatic of long-standing issues of communication and politicking where politics is not possible among the Russian elite.

Rather than a grand conspiracy and potential assassins in the Kremlin ready to depose Putin, the events of 23-24 June reflected an issue that’s long plagued the Russian regime: Putin’s perennial tactic of delegating a problem to multiple agents who may have their own, conflicting agendas.

This is Putin’s greatest instrument for maintaining his perch at the top of the Russian elite. It has long allowed the Russian leader to be seen as ‘above politics’. But in wartime, with Russia facing humiliation after humiliation and a coalition of much more powerful states, even loyalists (whether in the elite or in the street) see Putin as at best a ditherer, and at worst hostage to paranoia, faction-capture, and even conspiracy thinking. In essence, what happened in Russia at the weekend was an appeal to authority where the boss has checked out.

That said, a focus on Putin was not initially helpful as the ‘uprising’, or ‘bunt’ as some are calling it in Russian, unfolded. For me, Putin’s characteristic absence from the scene was useful to assess what all the state and para-state agencies would do – from Prigozhin’s ‘private’ military organisation Wagner, to the competing Defence Ministry, the Russian security services (also rivals to each other), ‘the Chechens’, and the Moscow government. A big question was: faced with what looked like an existential threat, would the Russian state start acting like one? People endlessly talked of defections and elite conspiracy, which was wide of the mark. Instead, we had something of a quasi-experiment to test the thesis about Russia’s supposed state weakness.

I have argued that the Russian state is ‘incoherent’, yet robust under pressure. When stretched, the Russian state has a certain improvisational elasticity so that it pings back – though not without breaking a lot of stuff in the process. What looks like chaos belies all kinds of unwritten rules and shared assumptions and values.

One of these shared assumptions is that the Russian elite and its factions, Prigozhin included, are not willing to confront Putin (yet). A coordinated defence of Moscow would have seen Prigozhin’s men exterminated.

Another hidden consensus is an allergy to internal strife – what looked like insurrection and lawlessness was actually relative constraint and calculation. Even a butcher and war criminal knows how to behave in his own home.

In a hugely revealing scene, on Saturday morning Prigozhin sat with two senior military leaders in Rostov before his drive north.

They were unarmed but not under arrest, while Prigozhin, demonstratively, was in full field dress. Speaking to camera, Prigozhin railed against the Russian establishment, not without cause. He guaranteed that the officials’ work in supplying the front would continue unimpeded. They appeared subdued and almost conciliatory. But at no point did they appear to make concessions. They kept hold of their image – for better and worse – as careermen of Russia’s militarised elite. Prigozhin, with his petulance, remained the outsider, seemingly aware that his clout rests only on the strategically useless, if not counterproductive, victory in a small town nobody in Russia cares about: Bakhmut. These are some of the contexts rarely heard, that are needed to understand what seems like an outlandish negotiated settlement between parties.

What to take away from these bizarre events – with the caveat that the Prigozhin story is not yet over? The much-derided Russian ‘state capacity’ needs much more careful unpacking. Even now, assumptions about the Russian state’s inability to organise may come back to haunt Ukraine and her allies.

Similarly, Russians are, in the main, disturbed by, or passively opposed to war. But that doesn’t mean there are internal mechanisms – even ones that propose rebellion – to change things at least in the short term. What we saw among the public in Rostov was not enthusiasm for Prigozhin and his war machine, but relief and post-shock euphoria. Russians know what they’ve done in Ukraine and how easily it could come home.

Finally, there’s the issue of our own crooked perspective: in a mediascape with little interest in expertise on Russia and Ukraine, uninformed and partisan voices are elevated; legacy media, desperate to remain relevant, merely serves to re-echo them.

We are all captured by events as they unfold because of platforms like Twitter. Big war accounts scrape posts from Telegram, which in turn feeds on Russian social media. Context gets divorced from context as unverified reports do the rounds. We get pictures of downed helicopters, men with their trousers around their ankles being arrested by other men with guns. Is this a scene of Prigozhin’s men arresting Russian officers? Is he shooting down his own country’s air force? Genuine open source intelligence usually clarifies with time. But in the meantime journalists and academics, consciously or not, become pundits, and often not very good ones.

Article also appeared at opendemocracy.net/en/odr/wagner-prigozhin-russia-putin-moscow/ bearing the following notice:

This article is published under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 licence. If you have any queries about republishing please contact us. Please check individual images for licensing details.

This article is published under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 licence. If you have any queries about republishing please contact us. Please check individual images for licensing details.