A Landmark Caspian Agreement — And What It Resolves

(Article ©2018 RFE/RL, Inc., Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty – rferl.org – – Bruce Pannier – August 9, 2018- also appeared at rferl.org/a/qishloq-ovozi-landmark-caspian-agreement–and-what-it-resolves/29424824.html)

It has taken more than 20 years. But on August 12, the leaders of Azerbaijan, Iran, Kazakhstan, Russia, and Turkmenistan will meet in the Kazakh port city of Aqtau, reportedly to sign a new convention on the legal status of the Caspian Sea.

An 18-page draft of the agreement, posted briefly on Russian Prime Minister Dmitry Medvedev’s website in June and obtained by RFE/RL, lists 24 articles, including territorial waters, maritime borders, rules for navigation, fishing rights, environmental matters, and, importantly, use of the sea’s resources.

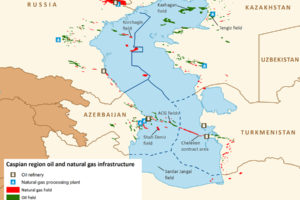

The Caspian seabed hides some 50 billion barrels of oil and nearly 9 trillion cubic meters of gas in proven or probable reserves. At current market prices, that is several trillion dollars’ worth of energy resources; with further exploration, it could turn out to be much more.

So it is perhaps unsurprising that it has taken this long to reach a deal on the Caspian’s legal status.

Debate has always hinged on whether the Caspian is a “sea” or a “lake.” It is an inland body of water, with no exits to any seas or oceans. The draft suggests the five littoral states will agree in Aqtau that the Caspian is a sea.

Classifying it as a lake would mean the resources of the Caspian should be divided equally among those five countries. The sea designation means the five countries should draw lines extending from their shores to the midway point with littoral neighbors.

Iran is arguably the loser under such an arrangement, as it would get only about 13 percent of the Caspian — and the deepest and saltiest part at that. That has seemingly led Tehran to resist any deal recognizing the Caspian as a sea.

Kazakhstan is seemingly the biggest winner under the “sea” definition, since more than half of the Caspian’s hydrocarbon wealth is said to lie in what would be Kazakhstan’s sector.

The absence of an agreement has not stopped Azerbaijan, Kazakhstan, Russia, and Turkmenistan from exploring and developing sections of the Caspian they have always believed to be their sectors. In that sense, the convention will formalize what was de facto already decided by those four countries years ago.

Last TCP Hurdle Cleared?

The intriguing part of the convention is Article 14, which according to the draft text states that “the parties can lay underwater pipelines along the Caspian floor” (Section 2) “according to consent by the parties through whose sector the cable or pipeline should be built” (Section 3).

Turkmenistan has wanted for more than 20 years to build a gas pipeline to ship its gas across the Caspian to Azerbaijan, where it would be pumped into pipelines leading west to Turkey or the Black Sea and, ultimately, to Europe.

Some felt that under international law, there was no obstacle to this Trans-Caspian Pipeline (TCP) being built — even without an agreement on the Caspian’s legal status from all five states — so long as Turkmenistan and Azerbaijan, through whose territories the pipeline would pass, approved the deal.

Russia and Iran have opposed the TCP on the grounds that it poses a potential environmental hazard to the Caspian’s unique biosphere. The claim seemed especially suspect from Russia, since Russia’s Gazprom has laid gas pipelines along the Black Sea to Turkey (Blue Stream) and is planning to build another one (TurkStream), and has also completed one pipeline across the Gulf of Finland to Germany (Nord Stream) and is hoping to build another pipeline to Germany (Nord Stream 2).

All those pipelines are said to be more technically challenging than construction of the TCP, and appear to face greater obstacles — the best example being unexploded bombs from World War II in parts of the Gulf of Finland.

Some felt Tehran and Moscow’s environmental concerns were actually economic concerns, stemming from the desire of each to hinder gas-exporting competitors, in this case Turkmenistan, from selling to markets in Europe. The European Union supports construction of the TCP and has included it as a potential part of the EU’s Southern Gas Corridor strategy.

Environmental Concerns

While Article 24, Section 2, of the draft allows littoral states to lay pipelines, it goes on to stipulate that such activities hinge on “the condition of the accordance of their projects with ecological demands and standards.”

It appears to be the same loophole that has held up construction of the TCP for all these years, though it is unclear whether this would represent an effective veto that other littoral states could employ to halt projects.

Other parts of the agreement hold individual countries responsible for any damage they cause to the sea through exploration, development of sites, or construction of platforms or pipelines, which seems to place the responsibility for safety on the parties involved in future hydrocarbon development or export projects.

There is a precedent for pipeline accidents in the Caspian. Two pipelines (one oil, one gas) leading from Kazakhstan’s offshore Kashagan site ruptured and leaked shortly after production started in September 2013. The other littoral states did not take any action, or even voice any criticism of Kazakhstan on that occasion.

However, it should be remembered that the Caspian Sea is home to sturgeon that produce the world’s finest caviar. Iranian Almas caviar, for example, is the most expensive in the world, selling for more than $30,000 per kilogram.

Turkmenistan has anticipated concerns about potential environmental damage to the Caspian and has hosted several recent conferences on ecological safety and publicly touted the efficient and thorough work of the country’s environmental organizations.

A report on August 8 on the Caspian Environmental Service (CaspEcoControl) in Turkmenistan “monitoring the environment, surface seawater and bottom sediments, groundwater of coastline, atmospheric air [and] analyzing the hydro-chemical regime in the sea at the stations located in Turkmenbashi Bay, Kiyanly Bay, Garabogaz, and Avaza.”

Kazakhstan and Azerbaijan also have plans to build the Kazakhstan Caspian Transportation System (KCTS) oil pipeline to bring Kazakh oil across the Caspian from the Kazakh port town of Quryq to Baku. If construction of that pipeline goes ahead, it is difficult to imagine that the TCP would not be built.

The agreement also forbids the presence on the Caspian of any military forces except those of the five littoral states. This part of the document would appear to favor Russia, which has by far the largest and most advanced naval force in the region.

The signing of the convention on the legal status of the Caspian would draw to a close nearly 22 years of work to reach an agreement. The document appears to resolve many of the problems that have given the littoral states, and potential foreign investors, pause when considering whether to go ahead with projects. But given the Caspian’s oil and gas wealth, it is unlikely this single document will settle all the differences that exist over the sea’s division and use of its resources.

[featured images not in original]