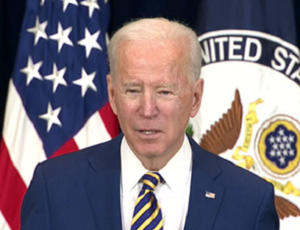

Survey: Experts Weigh In With Expectations for Biden-Putin Summit

(Russia Matters – russiamatters.org – June 15, 2021)

Five of America’s top Russia experts consider prospects for the June 16 meeting between presidents Joe Biden and Vladimir Putin in Geneva. Thomas Graham, Nikolas Gvosdev, Paul Kolbe, Olga Oliker and Angela Stent share their thoughts on stabilizing the U.S.-Russian relationship, low-hanging fruit, concrete steps to take and what can go wrong.

1. Should U.S. President Joe Biden seek normalization/stabilization of the U.S. relationship with Russia and why?

Thomas Graham

Senior Advisor, Kissinger Associates; Distinguished Fellow, Council on Foreign Relations

President Biden has set the right goal for relations with Russia: to deescalate tensions, to make them more stable and predictable. The continuing deterioration in relations is ever more fraught with the risk of igniting a direct conflict, which is in neither country’s interest. Moreover, the two nuclear superpowers share the primary responsibility for maintaining strategic stability. Although both have expressed their desire to launch talks on that issue, for progress to be made those talks need to be embedded in a broader U.S.-Russian dialogue as they were during the Cold War and immediate post-Soviet decades.

President Biden has set the right goal for relations with Russia: to deescalate tensions, to make them more stable and predictable. The continuing deterioration in relations is ever more fraught with the risk of igniting a direct conflict, which is in neither country’s interest. Moreover, the two nuclear superpowers share the primary responsibility for maintaining strategic stability. Although both have expressed their desire to launch talks on that issue, for progress to be made those talks need to be embedded in a broader U.S.-Russian dialogue as they were during the Cold War and immediate post-Soviet decades.

More normal diplomatic relations make sense for other reasons as well. They would help create conditions in which President Biden could focus on his top priorities, including such domestic tasks as economic recovery, democratic renewal and technological advance, as well as climate change. In addition, normalized relations would enable the United States to focus on the strategic challenge of China and could attenuate the current Sino-Russian strategic alignment. Finally, they would open up the possibility for more active global cooperation, including with both Russia and China, in dealing with urgent transnational challenges.

More normal diplomatic relations make sense for other reasons as well. They would help create conditions in which President Biden could focus on his top priorities, including such domestic tasks as economic recovery, democratic renewal and technological advance, as well as climate change. In addition, normalized relations would enable the United States to focus on the strategic challenge of China and could attenuate the current Sino-Russian strategic alignment. Finally, they would open up the possibility for more active global cooperation, including with both Russia and China, in dealing with urgent transnational challenges.

Nikolas Gvosdev

Professor of National Security Studies, U.S. Naval War College; Senior Fellow for Eurasia, Foreign Policy Research Institute

First, avoid terms like “normalization.” The competitive, adversarial nature of U.S.-Russia relations is no longer an aberration but the norm. What we need now is a way to regulate those interactions, a framework for discussions and encounters. The tactic of cutting off contact to protest and punish Russian actions has been counterproductive. Russia remains one of the few powers that can intersect U.S. interests across a broad geographic and functional agenda. In the crescent that runs from the Arctic to the Mediterranean to the Indian and Pacific oceans, Russia is a player; and it possesses a formidable nuclear and cyber arsenal. Contact is not a reward but a strategic necessity.

Mishandling Russia creates unnecessary and counterproductive tensions with U.S. partners in Europe and Asia whose cooperation is vital for American success on its two top foreign policy issues: China and climate. Russia can either be a positive or negative factor in both these areas. Working not toward “partnership” but toward some sort of modus vivendi is essential.

Paul Kolbe

Director, Intelligence Project, Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs

If normalized relations mean a return to regular communication on areas of agreement and disagreement, then certainly. However, normalized relations should not be confused with good relations, which will take time and significant changes in actions on both sides to achieve. Russia and the U.S. now view each other through a bitter and hostile lens.

The fact that the summit is taking place suggests that both the U.S. and Russia realize the extreme lack of direct contact between the two in recent years has contributed significantly to this state of dangerously low relations. For each, engagement offers an opportunity to communicate priorities, defend actions and, just possibly, identify areas of mutual interest if not agreement. Most important is that the U.S. and Russia return to a process that enables them to navigate through issues that could lead to unintended conflict and dangerous escalation.

Olga Oliker

Program Director, Europe and Central Asia, International Crisis Group

I think the answer depends in part on how one understands normalization and stabilization. If one thinks that normalization means a sort of alignment, that’s unrealistic for a wide range of reasons. If one is seeking a relationship in which Washington and Moscow can speak frankly about their many disagreements (and their few agreements) to ensure that they can genuinely understand one another’s red lines and intentions, a relationship in which their communication takes the form of direct dialogue with one another rather than public pronouncements, I think that would be very valuable and can, indeed, increase stability. While it won’t resolve the many disagreements, by any stretch, it might prevent misunderstandings.

Angela Stent

Director of the Center for Eurasian, Russian and East European Studies, Professor of Government and Foreign Service, Georgetown University

President Biden should seek the normalization of relations with Russia for several reasons. First, Russia became a disruptive domestic political issue during the Trump administration, inflaming our already polarized society, because of the 2016 election interference and because of questions about Trump’s own ties to Russia. The Biden administration’s goal is to remove Russia as a toxic domestic problem and focus on managing it as a foreign policy issue. That will enable the administration to pursue a more effective policy. Second, we need to restore full diplomatic ties between the two countries in order for this relationship to function and so that both sides understand what is happening in each other’s country. Third, we need to restore intergovernmental channels of communication that atrophied under Trump. As the world’s two nuclear superpowers and in a time of heightened global tensions it is imperative for both countries to try to manage their confrontation more effectively and diminish the chances of an unexpected clash. The administration says it would like to establish guardrails in this relationship—in other words, to come to enough of an agreement with Russia on key principles that the U.S. will be able to focus on other priorities—namely China—without having to deal with fires that frequently emanate from Russia. That would be the essence of normalization.

2. If Biden should seek normalization, what should be the first steps toward this goal and which of them can be taken at the summit? What are the low-hanging fruit, if any, for him and Russian President Vladimir Putin to pick in Geneva?

Thomas Graham

Senior Advisor, Kissinger Associates; Distinguished Fellow, Council on Foreign Relations

The summit should be focused primarily on two matters. First, each side needs to offer a clear articulation of its interests, red lines and expectations for relations. Second, the two sides should address, and ideally reach agreement on, a framework for sustained diplomatic engagement.

One concrete agreement could cover strategic stability talks, including the issues to be addressed and the starting date. Another possible, and necessary, concrete agreement could focus on the restaffing of the embassies in Washington and Moscow to the level necessary for sustained engagement, to include the issuance of visas in a timely fashion. Finally, the two sides could agree on what channels to create or continue to manage relations, including ones between the White House and Kremlin, the State Department and the Foreign Ministry and the military and intelligence services.

The dialogue would focus on both possible cooperation and contentious issues, but Geneva is not the place to make significant progress on any issue. That will come only as the dialogue develops.

Nikolas Gvosdev

Professor of National Security Studies, U.S. Naval War College; Senior Fellow for Eurasia, Foreign Policy Research Institute

The fact that the White House does not want to call this meeting a summit is instructive, because a summit implies an agenda and the possibility of making progress. We are nowhere near that level of preparedness, and eschewing a joint press conference also recognizes that achieving any sort of common ground in Geneva is highly unlikely. What is more important is that both leaders agree to a structure for conducting U.S.-Russia strategic stability talks and designate empowered individuals on both sides who have the authority to negotiate. After the confusion of the Trump years, where official statements and presidential tweets were often at cross purposes, establishing a clear channel of communication is imperative.

I don’t see low-hanging fruit to be harvested because almost every issue in U.S.-Russia relations has been reduced to zero-sum logic. Compromises are possible but they need time and quiet space to be negotiated, and the glare of Geneva is not the place. This is why this is not a “summit” in the pure sense of the term. As long as both presidents can leave the meeting, shake hands and indicate the start of a dialogue, Geneva can be considered a success.

Paul Kolbe

Director, Intelligence Project, Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs

First steps include the one implicit in the summit: an agreement to meet and talk despite disagreement. This should continue. While the U.S. and Russia fundamentally differ on many issues and are unlikely to come to any agreement at this summit, it is in U.S. (and Russian) long-term strategic interests to draw Russia more closely to the West and away from China. Small steps might include commitment to build on extension of the New START agreement, to counter international cybercrime, to not use cyber to mess with nuclear command and control systems and to reject interference in each other’s electoral processes (without admission of past interference). Climate change might offer another area for exploration. As the world’s leading oil and gas producers, both Russia and the U.S. face the challenge of how to support efforts to combat climate change while not undermining their own economies and competitiveness. Russia, in particular, faces a difficult future in a decarbonizing world.

Olga Oliker

Program Director, Europe and Central Asia, International Crisis Group

Both Moscow and Washington have taken pains to keep expectations for the summit low. Both capitals have also engaged in some rhetoric leading up to it to show strength, and indicate that they aren’t heading to Geneva with the intent to compromise. I therefore think that from a public standpoint, the very best we can hope for is commitments to cooperate on climate change, vaccine distribution and strategic stability and arms control (perhaps including cybersecurity). The latter will likely mean continued consultations, but perhaps with the intent to work toward a treaty. At the same time, I think the summit presents a crucial opportunity to engage in the kind of dialogue I mentioned in the first response, but without the fanfare and public pronouncements. Both presidents can make their red lines and repercussions for crossing them clear. In that context, they can, and should, talk about all the issues that divide them, including Ukraine, Syria, Belarus and even Russia itself.

Angela Stent

Director of the Center for Eurasian, Russian and East European Studies, Professor of Government and Foreign Service, Georgetown University

The first step is to restore full diplomatic ties so that both of our ambassadors can return and contacts can be re-established. Both presidents can agree to that during the meeting. A more difficult issue is Russia’s designation of the U.S. as an “unfriendly country” and its intent to prohibit Russians and other third-country nationals from working in the U.S. Embassy. This has virtually shut down the consular section and prevented the issuing of visas to Russians. Some compromise must be found here. Another “low-hanging fruit” is the mutual commitment to restart strategic stability talks. Both sides are in favor of it and preliminary discussions have already begun. Of course, strategic stability is a protean concept and one challenge will be to agree about what to discuss. Non-strategic nuclear weapons? Missile defense? Regional conflicts? Cyber? The list is quite long. Climate change is something that both leaders acknowledge as a serious problem and they could agree to work together on climate issues. The Arctic presents some possibilities for engagement. They will surely discuss Iran as the U.S. and Russia have been working together with Europe and China to facilitate America rejoining the JCPOA.

3. If Biden should not seek normalization/stabilization of the U.S. relationship with Russia, then what should he seek to achieve when he meets Putin?

Thomas Graham

Senior Advisor, Kissinger Associates; Distinguished Fellow, Council on Foreign Relations

If restoration of more normal diplomatic contacts is not Biden’s goal or proves unattainable, his primary goal in Geneva should be to ensure that Putin understands clearly America’s red lines and determination to counter through whatever means necessary Russian actions that cross those lines or otherwise threaten America’s national interests, to include relations with our allies and partners.

Nikolas Gvosdev

Professor of National Security Studies, U.S. Naval War College; Senior Fellow for Eurasia, Foreign Policy Research Institute

No “reset” of relations is possible at this point, and we should understand “normalization” not as the absence of competition but as finding a way to prevent competition from tipping over into conflict. Nor should we expect that the three decades of relatively chilly personal relations between Biden and Putin will be transformed into a sudden friendship.

One problem we’ve had in the past is that the U.S. side consistently underestimates the sources of Russian strength and power (while overestimating Moscow’s problems). For its part, the Kremlin consistently miscalculates how its actions will be received in Washington. Ideally, this meeting can help to dispense with illusions, and particularly for both presidents to have a frank discussion—not with the goal of convincing the other of the rightness of their position, but to understand sources of motivation and determination. These miscalculations are why I believe the Russian interventions in Ukraine and Syria caught Americans by surprise, while the Russians failed to understand why it was so difficult for Americans to let the 2016 election be bygones.

Paul Kolbe

Director, Intelligence Project, Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs

Whether President Biden seeks normalized relations or not, his first priority is to gain Putin’s attention and respect. This is best done by consistent and sustained demonstration of strength and will. Elements of this include reinvigoration of NATO, support to Ukraine’s territorial sovereignty and credible ability to spot and counter Russian efforts to pry apart allies abroad and citizens at home. Putin is likely to be in power long past a Biden presidency, and past the Democrats’ hold on the White House and Congress. Putin must be convinced that U.S. policy and actions on Russia are built to last across successive administrations, much as the U.S. held a bipartisan consensus on countering Soviet influence and expansion through five decades of cold war.

Russia is not the United States’ main strategic problem or priority, but it is nonetheless an important one. In the past, the U.S. has made the mistake of expecting that Russian and American interests would closely align, then dismissing and ignoring Russia when they didn’t. This didn’t cause problems to disappear but instead to fester.

In that respect, should Biden seek to more assertively deter and counter malign Russian actions, there is value in directly communicating U.S. intent and priorities to President Putin. Public and private messages must align, as well as actions with words. At the same time, where it is possible to reward changes in behavior, U.S. actions should flex in response. The U.S. should first and foremost focus on rallying allies to demonstrate that odious actions such as assassination, arbitrary arrests of U.S. and allied citizens, elections interference and instigation of violence in Ukraine will be consistently and predictably exposed and opposed.

4. What can go wrong?

Thomas Graham

Senior Advisor, Kissinger Associates; Distinguished Fellow, Council on Foreign Relations

The results of the summit could inadvertently create the impression that there has been a reset in relations. The restoration of more normal diplomatic relations, however, is not about building a partnership or a return to business as usual; it is about creating structures to manage responsibly what remains an adversarial relationship. Some critics, however, will be inclined to discredit this restoration as a misguided reset based on unwarranted concessions to Putin and naivety about Putin’s goals and interests. To minimize this risk, the administration needs to conduct the summit in a way that makes clear no reset is intended—no joint press conference and/or a joint statement that clearly identifies areas of continuing contention, for example. It also needs to be prepared to counter firmly in its post-summit public statements and actions accusations that it has reset relations with Russia.

Nikolas Gvosdev

Professor of National Security Studies, U.S. Naval War College; Senior Fellow for Eurasia, Foreign Policy Research Institute

The pre-meeting landscape is already quite negative. The media and a number of public figures and legislators almost seem to want the Geneva meeting to be some version of the famous Cold War-era “Two Tribes” music video released by the British musical group Frankie Goes to Hollywood, where the two presidents battle it out. The calls for Biden to essentially stick his finger in Putin’s chest, call him a killer and demand immediate compliance with a list of U.S. preferences (starting with returning Crimea to Ukraine) would make this meeting a non-starter.

It is important for Putin and Biden to be able to speak frankly and openly to each other, but if they speak to the cameras for their domestic audiences, hopes that this meeting can create a framework for ongoing U.S.-Russia dialogue will be dashed.

Paul Kolbe

Director, Intelligence Project, Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs

Well, the summit can’t get much worse for either side than Helsinki, so there’s that. With expectations low, and each side sending out positive but cautious signals, it is unlikely that the meetings will go catastrophically off the rails.

From a U.S. perspective what can go wrong is that it falls into the traps of the past.

Russia has benefited from stable leadership and a consistent strategy vis-à-vis the United States for over 20 years. The U.S., on the other hand, has literally been all over the map. Wild policy swings during and between successive U.S. administrations have played into Russian interests, doing much of Putin’s work for him. At the most basic level, the U.S. cannot hope for a more normal and predictable relationship with Russia if its own policy approach is inconsistent and unstable. The challenge for Biden, then, is to present Putin with a U.S. stance that is credible and sustainable. Recent bipartisan initiatives on China provide a good example of an approach that might be taken with regard to Russia, recognizing it as a strategic competitor but focusing on actions that strengthen our own competitive base.

Olga Oliker

Program Director, Europe and Central Asia, International Crisis Group

I think we have escaped the threat of unrealistic expectations, at least, with this particular summit. No one expects much, so anything is a victory. But very harsh rhetoric from both at the summit, particularly if it is not paired with quiet understandings behind the scenes, would likely escalate tensions. On the flip side, misunderstood or misreported private pledges would have their own downsides, though perhaps not as immediately. For that reason, it would be wise to make sure that everyone walks away with a common understanding. I suppose another possibility is that very little comes out of this summit and, as a result, discussion and communication channels shut down in frustration.

Angela Stent

Director of the Center for Eurasian, Russian and East European Studies, Professor of Government and Foreign Service, Georgetown University

The Biden administration seeks a “stable and predictable” relationship with Russia. But is that what Russia wants? The Kremlin has benefited from the unpredictability of its foreign policy, as the latest massing of troops on the Ukrainian border proved, when both the U.S. and Ukraine were concerned about an imminent invasion. Russia threw other countries off balance. For Putin, this summit will represent a reaffirmation of Russia’s position as a great power that cannot be isolated by the West—and a signal to China that Russia has its own sovereign foreign policy options. But Biden will no doubt raise contentious issues—Ukraine, Belarus, Russia’s state-sponsored cyber intrusions and harboring of cyber criminals, the treatment of Alexei Navalny and the repression of the political opposition. Putin will bring up the Russian litany of violations of human rights in the U.S., including those of the January 6th insurrectionists at the U.S. Capitol. The discussions could deteriorate into rancor and could break off in disagreement. Having said that, both presidents are seasoned professional politicians and will probably ensure that there is a face-saving outcome.

Article also appeared at russiamatters.org/analysis/survey-experts-weigh-expectations-biden-putin-summit, with different images, bearing the notice: “© Russia Matters 2018 … This project has been made possible with support from Carnegie Corporation of New York,” with a footer heading entitled “Republication Guidelines” linking to: russiamatters.org/node/7406, which bears the notice, in part:

“If you would like to reprint one of these articles, a blog post written by RM staff, one of our infographics or a fact-check, we ask that you follow these guidelines:

- Include a prominent attribution to Russia Matters as the source and link back to the original at RussiaMatters.org.

- Retain the hyperlinks used in the original content.

- Do not change the meaning of the article in any way.

- Get an ok from us for non-substantive changes like partial reprints or headline rewrites and inform readers of any such modifications (e.g., This article first appeared on the Russia Matters website with the headline “Russian Election Interference in Trump’s Own Words”).

- Let us know about the reprint and send a link!

Please note that Russia Matters cannot grant permissions for third-party content, including articles, photographs and other materials not produced by our team.

Questions? Email us at RussiaMatters@hks.harvard.edu.”