RUSSIALIST: “Andrei Zorin’s Biography ‘Leo Tolstoy’ is Essential Reading; This slim but rich volume is impossible to put down” – Moscow Times

(Moscow Times – themoscowtimes.com – Michele A. Berdy – Sept. 26, 2021)

Michele A. Berdy is the Arts Editor and author of “The Russian Word’s Worth,” a collection of her columns.

Leo Tolstoy’s life and works are copiously documented in editions of his writings in dozens of languages, new translations, biographies, critical studies, diaries and memoirs written by Tolstoy himself, his family, and his friends. If you already have several shelves bending under all these Tolstoys and about-Tolstoys, do you need another biography?

Leo Tolstoy’s life and works are copiously documented in editions of his writings in dozens of languages, new translations, biographies, critical studies, diaries and memoirs written by Tolstoy himself, his family, and his friends. If you already have several shelves bending under all these Tolstoys and about-Tolstoys, do you need another biography?

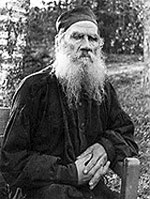

If it’s Andrei Zorin’s “Leo Tolstoy,” the answer is yes. Written first in English and then translated by the author into Russian, this slim volume — less than 200 pages — takes you through Tolstoy’s life and work with a light touch but remarkable breadth of knowledge. It consists of four chapters that represent blocks of time, work and focus and to some extent the roles that Tolstoy played: An Ambitious Orphan, A Married Genius, A Lonely Leader, and A Fugitive Celebrity. But, as Zorin shows us, despite different incarnations — from an army officer to an ardent pacifist, from drinking tea in aristocratic drawing rooms to pulling a plough in peasant garb, from brothels and dalliances with servants to a close-knit family life (however dysfunctional) — Tolstoy was remarkably consistent, if sometimes he was consistent in his internal war of conflicting beliefs and desires.

Behavior that troubled him in life became the subject of his fiction. In “Childhood,” Zorin writes, “…Tolstoy shifted to the reconstruction of the thoughts, feelings and perceptions of a ten-year-old boy, one of the first such endeavors in world literature. Placing his book on the thin borderline between the autobiographical and fictional, he managed to present his personal experience as universal without losing a feeling of total authenticity. Later this technique would become the unmistakable trademark of Tolstoy’s narratives.”

He used his family and friends as models for his fictional characters. “‘I took Tanya [his sister-in-law], added Sonya [his wife], stirred it up and got Natasha’ once said Tolstoy listing the ingredients of his most charming female character…”

But then, as Tolstoy wrote and “edited” — which was actually waves of rewriting — the characters took on lives of their own.

For example, in an early version of “Anna Karenina,” Zorin writes that Anna “is a lascivious animal, not so much morally corrupt as inherently immoral. The other characters see her as possessed by a ‘devil, ’an evil for

ce or, in Schopenhauerian terms, the will to live. When she gets pregnant by Udashev (Vronsky ), Anna’s wet eyes shine with happiness. As was by now his custom, Tolstoy made things more subtle and less straightforward as he rewrote the novel. If the ‘will to live’ or ‘force of life,’ as Tolstoy called it in the epigraph to one of the chapters, is irresistible, how could one possibly blame Anna?”

Zorin, who is a cultural historian and chair of Russian at Oxford University, brings his rich knowledge of Russia’s political life and personalities, philosophical, social and religious trends to his task. He places Tolstoy’s anarchism in context, writing “Tolstoy was a contemporary and a compatriot of such leading figures in the history of European anarchism as Mikhail Bakunin and Piotr Kropotkin. All three of them were aristocratic intellectuals who looked for ideals in the life of Russian peasant communes, in the stubborn resistance of sectarians and Old Believers to the official Church and central authorities, in Cossack settlements providing military support to the crown, but defying state bureaucracy in their way of life. No less important for Tolstoy were the numberless wanderers, pilgrims and beggars who left their homes and villages to search for God. The utopian vision of life without a state, masters or an official Church is no less important for Russian intellectual tradition and popular aspirations than its antithesis: unswerving trust in the secular and spiritual authorities.Tolstoy and Dostoevsky represented the two trends.”

And so we follow Tolstoy, dipping into his novels and other writing — Zorin’s serious treatment of his treatises and educational materials is particularly interesting — pausing for some help understanding the political situation or Russian cultural values, as he heads inexorably to the train station in Astapovo. There in his flight from his family and all that tethered him to everyday life, he becomes ill and is taken into the little station house where he inadvertently gives the world its first glimpse of the cult of celebrity in the future. “Within a day,” Zorin writes, “the little railway station became the main provider of breaking news to the whole world from Japan to Argentina. Reporters, photographers, cameramen, government officials, police agents, admirers and gawpers started swarming to Astapovo. Tolstoy’s flight brought him further into the limelight. Trying to evade the advance of modernity, he had contributed to its triumph by creating one of the first global media events.”

He would have hated it, had he known.

[article also appeared at themoscowtimes.com/2021/09/26/andrei-zorins-biography-leo-tolstoy-is-essential-reading-a75122]