Ukraine and NATO: Disconnect Between State Policy and Public Opinion Is Less Dangerous Than Russia

(Russia Matters – russiamatters.org – Daniel Shapiro – May 9, 2019 – russiamatters.org/analysis/ukraine-and-nato-disconnect-between-state-policy-and-public-opinion-less-dangerous-russia)

Daniel Shapiro is a graduate student at Harvard University specializing in contemporary Russian politics, Russian public/private sector relations and the North and South Caucasus. He is also a graduate student associate with Russia Matters.

Newly elected Ukrainian president Volodymyr Zelenskiy has repeatedly reaffirmed his predecessor’s policy of bringing Ukraine ever closer to Europe and has said that, as a citizen, he supports his country’s accession to NATO. However, unlike Petro Poroshenko, Zelenskiy insists the question of joining the Western military alliance should be decided by a popular referendum. Indeed, today the idea of NATO accession is far from universally popular in Ukraine. As Poroshenko’s other political opponents have pointed out, opinion polls consistently show that about a third of Ukrainians oppose entry into the bloc—even after Russia’s military intervention of 2014. (See table below.) Zelenskiy has claimed that “Europeans” entered NATO only “when they knew that a very high percentage—80 percent [of the public] in some countries—was for NATO.”

Newly elected Ukrainian president Volodymyr Zelenskiy has repeatedly reaffirmed his predecessor’s policy of bringing Ukraine ever closer to Europe and has said that, as a citizen, he supports his country’s accession to NATO. However, unlike Petro Poroshenko, Zelenskiy insists the question of joining the Western military alliance should be decided by a popular referendum. Indeed, today the idea of NATO accession is far from universally popular in Ukraine. As Poroshenko’s other political opponents have pointed out, opinion polls consistently show that about a third of Ukrainians oppose entry into the bloc—even after Russia’s military intervention of 2014. (See table below.) Zelenskiy has claimed that “Europeans” entered NATO only “when they knew that a very high percentage—80 percent [of the public] in some countries—was for NATO.”  Recent history paints a different picture: Governments in plenty of countries—from the Czech Republic and Latvia to the Balkans—have pushed through major foreign policy initiatives such as NATO entry despite formidable opposition among their citizens. Below we examine four cases in which governments enacted major foreign-policy decisions related to NATO membership that diverged from public opinion—and no waves of unrest followed. This is not meant to either advocate for Ukraine’s NATO entry or oppose it, but to review precedents. In reality, Kiev likely has good reason to proceed with extreme caution in pursuing its NATO aspirations: Russia would see Ukraine’s entry into the bloc as a direct threat to its own national security and has already demonstrated its willingness to use force to keep Ukraine from “escaping” to the West. In the other cases, Moscow never welcomed the idea of NATO expansion, but seemed, as Simon Saradzhyan has argued, to make the calculation that either the threat to its national interests was not sufficiently acute or the chances for a successful military intervention were too slim.

Recent history paints a different picture: Governments in plenty of countries—from the Czech Republic and Latvia to the Balkans—have pushed through major foreign policy initiatives such as NATO entry despite formidable opposition among their citizens. Below we examine four cases in which governments enacted major foreign-policy decisions related to NATO membership that diverged from public opinion—and no waves of unrest followed. This is not meant to either advocate for Ukraine’s NATO entry or oppose it, but to review precedents. In reality, Kiev likely has good reason to proceed with extreme caution in pursuing its NATO aspirations: Russia would see Ukraine’s entry into the bloc as a direct threat to its own national security and has already demonstrated its willingness to use force to keep Ukraine from “escaping” to the West. In the other cases, Moscow never welcomed the idea of NATO expansion, but seemed, as Simon Saradzhyan has argued, to make the calculation that either the threat to its national interests was not sufficiently acute or the chances for a successful military intervention were too slim.

Ukrainian Public Opinion

Between 2013 and 2018, polls showed that 35 to 55 percent of the Ukrainian public supported NATO accession for their country. Since 2014, when Russia annexed Crimea and threw its support behind separatists in eastern Ukraine, those in favor of NATO entry have outnumbered those opposed to it in 24 of 25 polls reviewed below, but the majority has been slim and only four polls out of 30 have shown half of Ukrainians or more supporting accession.1

Between 2013 and 2018, polls showed that 35 to 55 percent of the Ukrainian public supported NATO accession for their country. Since 2014, when Russia annexed Crimea and threw its support behind separatists in eastern Ukraine, those in favor of NATO entry have outnumbered those opposed to it in 24 of 25 polls reviewed below, but the majority has been slim and only four polls out of 30 have shown half of Ukrainians or more supporting accession.1

| Pollster | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 |

| Gorshenin Institute | For: 35.3; Against: 43.2 | For: 53.4; Against: 33.6 | For: 54.1; Against: 33.1 | For: 47.1; Against: 35.4 | For: 46.1; Against: 33.4 | For: 50.5; Against: 33.2 | |

| Rating | For: 51; Against: 25 | For: 46; Against: 30 | For: 47; Against: 31 | For: 45; Against: 33 | For: 44; Against: 36 | ||

| Kiev International Institute of Sociology (KIIS) | For: 47.8; Against: 32.4 | For: 43.3; Against: 33.4 | For: 43.9; Against: 38 | For: 44.8; Against: 27.2 | For: 41.4; Against: 37.8 | ||

| Razumkov Centre | For: 36.7; Against: 41.6 | For: 43.3; Against: 31.6 | For: 44.3; Against: 38.1 | For: 43.2; Against: 33.3 | For: 46.3; Against: 31.6 | ||

| International Republican Institute | For: 43; Against: 31 | For: 48; Against: 30 | For: 45; Against: 30 | For: 46; Against: 27 | For: 43; Against: 33 | ||

| Ilko Kucheriv Democratic Initiative Foundation | For: 16.2; Against: 60.6 | For: 48.8; Against: 32.8 | For: 47.8; Against: 34.3 | For: 48.1; Against: 33.4 | For: 44.1; Against: 39.3 |

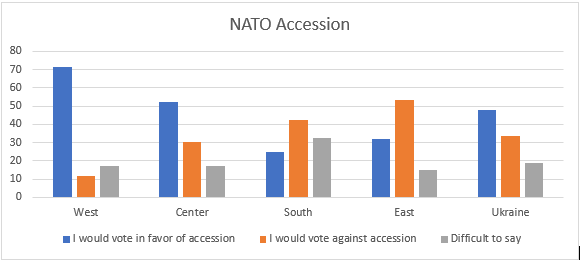

Moreover, Ukraine is divided over the NATO issue. As Zelenskiy—who himself managed to overcome the country’s geographical divide in the final round of voting—has noted, the west of the country is generally supportive of accession and the east less so: “I want to unite the country,” he said in an interview days before winning office. In this case, poll numbers do support his impressions: According to a 2017 report by the Ilko Kucheriv Democratic Initiatives Foundation, there was stark regional variation in answers to the question, “If you participated in a referendum on accession to NATO, how would you vote?”—with support for NATO entry in the country’s west exceeding that in the east and south by about 40-45 percentage points. (See table.)

| West | Center | South | East | Ukraine | |

| I would vote in favor of accession | 71.3 | 52.3 | 24.7 | 31.9 | 48.1 |

| I would vote against accession | 11.5 | 30.3 | 42.6 | 53.1 | 33.4 |

| Difficult to say | 17.3 | 17.4 | 32.7 | 15.0 | 18.6 |

Case 1: Czech Republic

The Czech Republic was officially invited to join NATO in 1997 and entered in 1999, with levels of public support similar to today’s figures in Ukraine: In 1997, 43 percent of Czechs supported NATO entry; following NATO’s official invitation for Prague to join the alliance, support rose and stabilized slightly above 50 percent. Five polls from 1998 show numbers between 50 and 55 percent—comparable to three Ukrainian polls from 2014-2015. Various political groups opposed joining NATO, largely due to fears that the Czech Republic’s sovereignty would be compromised, that accession would antagonize Russia, that admission would lead to higher defense costs and for other reasons. Despite these concerns and the underwhelming levels of public support, the accession process ran smoothly. Moscow was certainly not happy about NATO expansion at the time, but utterly lacked the capacity to stop it by force.

The Czech Republic was officially invited to join NATO in 1997 and entered in 1999, with levels of public support similar to today’s figures in Ukraine: In 1997, 43 percent of Czechs supported NATO entry; following NATO’s official invitation for Prague to join the alliance, support rose and stabilized slightly above 50 percent. Five polls from 1998 show numbers between 50 and 55 percent—comparable to three Ukrainian polls from 2014-2015. Various political groups opposed joining NATO, largely due to fears that the Czech Republic’s sovereignty would be compromised, that accession would antagonize Russia, that admission would lead to higher defense costs and for other reasons. Despite these concerns and the underwhelming levels of public support, the accession process ran smoothly. Moscow was certainly not happy about NATO expansion at the time, but utterly lacked the capacity to stop it by force.

Case 2: Montenegro

Montenegro’s move toward NATO, including an application for a membership action plan in 2008 and culminating in accession in 2017, also enjoyed only lukewarm public support—cooler even than in Ukraine. According to the Montenegrin think tank Center for Democracy and Human Rights (CEDEM), which conducted regular opinion polls on NATO accession, public support gradually increased from 26.9 percent in 2008 to 39.7 percent in December 2016. An October 2017 poll from the International Republican Institute (IRI), meanwhile, indicated 43 percent support for NATO membership,[2] while another CEDEM poll from December 2018 showed 40 percent support.

Like Ukrainians, Montenegrins have been divided on NATO and there are grounds to believe Russia tried to exacerbate these divisions. Accession and membership is highly unpopular with Montenegro’s ethnic Serbs—who made up 28.7 percent of the population according to the 2011 census—in part because they strongly condemned the bloc’s 1999 bombings of Yugoslavia. The Montenegrin parliament’s vote in favor of NATO accession in April 2017 was met with protests; 35 of the country’s 81 lawmakers had boycotted the session in opposition to the majority’s stance. In October 2016 the country saw an attempt to overthrow its pro-NATO government, with 13 individuals, including two Russian nationals with alleged ties to Russian military intelligence, convicted of the attempted coup earlier this month. However, the coup organizers failed to win popular support and the Montenegrin political climate has remained relatively calm, although public support for NATO appears to be declining of late.

Case 3: Latvia

Latvia, like Montenegro, has distinct ethnic cleavages that correlate with attitudes toward NATO: A year before the country’s accession to NATO in 2004, a RAND Corporation testimony to Congress cited polls showing that 68.5 percent of all Latvians supported NATO entry in December 2002—quite a high number. However, while well-supported by ethnic Latvians, accession was reportedly largely opposed by the country’s significant Russian minority (25.2 percent of the population in 2018). The sharp divide in opinion persists: According to a 2016 report from Latvian Public Broadcasting, while 73 percent of Latvian speakers support their country’s NATO membership, only 38 percent of ethnic Russians living in Latvia do and 48 percent oppose it. Again Moscow strongly opposed the expansion of NATO into its Soviet-era domain; however, the Kremlin—still working at the time to consolidate its hold on the country’s levers of governance—decided that military intervention was not in the country’s best interests, perhaps both because it deemed the chances for victory insufficiently high and because the Russian leadership was then pursuing a more conciliatory policy toward the West.

Latvia, like Montenegro, has distinct ethnic cleavages that correlate with attitudes toward NATO: A year before the country’s accession to NATO in 2004, a RAND Corporation testimony to Congress cited polls showing that 68.5 percent of all Latvians supported NATO entry in December 2002—quite a high number. However, while well-supported by ethnic Latvians, accession was reportedly largely opposed by the country’s significant Russian minority (25.2 percent of the population in 2018). The sharp divide in opinion persists: According to a 2016 report from Latvian Public Broadcasting, while 73 percent of Latvian speakers support their country’s NATO membership, only 38 percent of ethnic Russians living in Latvia do and 48 percent oppose it. Again Moscow strongly opposed the expansion of NATO into its Soviet-era domain; however, the Kremlin—still working at the time to consolidate its hold on the country’s levers of governance—decided that military intervention was not in the country’s best interests, perhaps both because it deemed the chances for victory insufficiently high and because the Russian leadership was then pursuing a more conciliatory policy toward the West.

Case 4: Greece

Another recent instance in which a government disregarded public opinion on a major foreign policy issue concerned NATO entry indirectly: In June 2018, the Greek government reached a highly unpopular deal with its northern neighbor Macedonia allowing the latter to rename itself the “Republic of North Macedonia” and advance its attempts to join NATO and the European Union, which had stalled due to the naming dispute. The argument over what can be called “Macedonia”—the former Yugoslavian republic or the eponymous region in northern Greece—had stretched on for decades, flaring after (now North) Macedonia got its independence: In 1992, over one million Greeks took to the streets to protest the use of “Macedonia” in the newly independent country’s name. This opposition has continued to the present day: As of September 2016, 57 percent of Greeks wanted North Macedonia’s new name to have no reference whatsoever to the word “Macedonia”; by June 2018, this figure had risen to 68 percent. However, that same month, Greek Prime Minister Alexis Tsipras signed a deal with his Macedonian counterpart to officially agree on the name change. While the move did cost Tsipras’ Syriza party political points, he has managed to hold on to power thus far. Russia vocally opposed the name change and Greece expelled Russian diplomats on allegations that they had tried to foment opposition inside the country, but Moscow showed no interest in pursuing a military solution.

Another recent instance in which a government disregarded public opinion on a major foreign policy issue concerned NATO entry indirectly: In June 2018, the Greek government reached a highly unpopular deal with its northern neighbor Macedonia allowing the latter to rename itself the “Republic of North Macedonia” and advance its attempts to join NATO and the European Union, which had stalled due to the naming dispute. The argument over what can be called “Macedonia”—the former Yugoslavian republic or the eponymous region in northern Greece—had stretched on for decades, flaring after (now North) Macedonia got its independence: In 1992, over one million Greeks took to the streets to protest the use of “Macedonia” in the newly independent country’s name. This opposition has continued to the present day: As of September 2016, 57 percent of Greeks wanted North Macedonia’s new name to have no reference whatsoever to the word “Macedonia”; by June 2018, this figure had risen to 68 percent. However, that same month, Greek Prime Minister Alexis Tsipras signed a deal with his Macedonian counterpart to officially agree on the name change. While the move did cost Tsipras’ Syriza party political points, he has managed to hold on to power thus far. Russia vocally opposed the name change and Greece expelled Russian diplomats on allegations that they had tried to foment opposition inside the country, but Moscow showed no interest in pursuing a military solution.

The Russia Factor

So where do these examples leave Ukraine?

So where do these examples leave Ukraine?

On one hand, they suggest that moving toward NATO wouldn’t trigger some sort of uprising among those Ukrainians who oppose such a move (though a coup attempt cannot be ruled out). The experience of other nations shows that democratically elected governments can push through momentous foreign-policy decisions despite public opposition and stay in power. Moreover, in modern-day Ukraine, there is some measure of elite consensus on moving toward NATO: The policy was enshrined in the constitution early this year; the new president has reaffirmed it; and parliament is largely united on the issue.

On the other hand, inching toward NATO would likely be more dangerous for Ukraine than the policy decisions examined above—not because of the discrepancy between politicians’ decisions and public opinion, but because of Russia: Moscow fears that its neighbor’s “escape” to the West would pose a significant threat to Russian security and today it has both the capacity and the motivation to forcefully prevent Ukraine from implementing a decision to join NATO. Russia has already used force once in response to Ukraine’s 2014 gear shift toward NATO—annexing Ukrainian territory, sending in troops and providing crucial material support to separatists in the east. The conflict has claimed more than 10,000 lives and prospects for reconciliation have been looking bleak, both on the international front and domestically. Meanwhile, President Vladimir Putin has made it clear that Russia continues to see Ukrainian accession to NATO as a “direct and immediate threat for [its] national security” and would react to Ukraine’s joining the alliance “very negatively.” NATO states now seem to understand that Ukraine is “the reddest of red lines” for Moscow, as diplomat William Burns has called it, and that Russia is willing not only to disrupt its neighbor but to play spoiler against the bloc’s members. This suggests that—whatever the results of Zelenskiy’s referendum—the chances that all NATO members would greenlight membership talks with Ukraine (and consensus is required) are relatively slim.

Footnotes

- The table shows the highest level of support for or opposition to NATO accession for each polling organization in a given year. The months the polls were taken, as well as other figures from each year, can be found here. Hyperlinks are given when data has been posted online; other figures were provided by the pollsters.

- This poll concerns Montenegro’s membership in NATO, not its accession, as Montenegro joined NATO in June 2017.

Article also appeared at russiamatters.org/analysis/ukraine-and-nato-disconnect-between-state-policy-and-public-opinion-less-dangerous-russia, with different images, bearing the notice: “© Russia Matters 2018 … This project has been made possible with support from Carnegie Corporation of New York,” with a footer heading entitled “Republication Guidelines” linking to: russiamatters.org/node/7406, which bears the notice, in part:

“If you would like to reprint one of these articles, a blog post written by RM staff, one of our infographics or a fact-check, we ask that you follow these guidelines:

- Include a prominent attribution to Russia Matters as the source and link back to the original at RussiaMatters.org.

- Retain the hyperlinks used in the original content.

- Do not change the meaning of the article in any way.

- Get an ok from us for non-substantive changes like partial reprints or headline rewrites and inform readers of any such modifications (e.g., This article first appeared on the Russia Matters website with the headline “Russian Election Interference in Trump’s Own Words”).

- Let us know about the reprint and send a link!

Please note that Russia Matters cannot grant permissions for third-party content, including articles, photographs and other materials not produced by our team.

Questions? Email us at RussiaMatters@hks.harvard.edu.”