The galloping militarisation of Eurasia

(opendemocracy.net – Neil Melvin – June 16, 2014)

Neil Melvin is director of the Armed Conflict and Conflict Management Programme at SIPRI

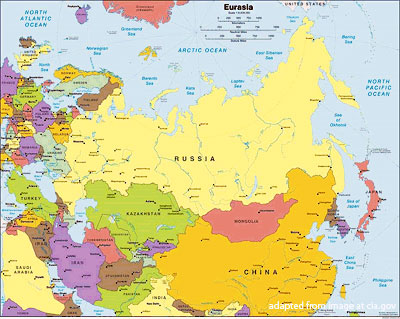

In recent months, attention has overwhelmingly been focused on Moscow’s actions in Ukraine. But there is a wider and more disturbing process of militarisation underway throughout the Eurasian region.

Russia’s annexation of the Crimean peninsula and the deployment of up to 40 000 troops on Ukraine’s border to support the actions of pro-Russian separatist forces, has been widely identified as a turning point in the ‘post-Cold War’ European security system. But Russia’s militarised policy towards Ukraine should not be seen as a spontaneous response to the crisis – it has only been possible thanks to a long-term programme by Moscow to build up its military capabilities.

A 21st century Russian military

To be a ‘great power’ – which is the status that Moscow’s political elite claim for Russia – is to have both an international reach and regional spheres of influence. To achieve this, Moscow understands that it must be able to project military force, and so the modernisation of Russia’s armed forces has become a key element of its ‘great power’ ambitions. For this reason, seven years ago, a politically painful and expensive military modernisation programme was launched to provide Russia with new capabilities. One of the key aims of this modernisation has been to move the Russian military away from a mass mobilisation army designed to fight a large-scale war (presumably against NATO) to the creation of smaller and more mobile combat-ready forces designed for local and regional conflicts.

The size of Russia’s armed forces is being cut from 1.2m to around 1m, the officer corps is being slimmed by almost 50%, and a cadre of well-trained NCOs is being created. Conscription will remain, but better pay and conditions are intended to create a more professional army. The reforms have replaced the old four-tier command system of military districts, armies, divisions, and regiments with a two-tier structure of strategic commands and leaner, more mobile combat brigades.

Increased defence budgets

But reorganisation has not been the only priority. Buoyed by the wealth pouring into the state coffers from oil and gas sales, Russia has sought to upgrade its ageing Soviet equipment. In 2010, Russia launched an ambitious ten-year weapons modernisation programme at a total estimated cost of $720 billion. The aim is to go from a situation in the last decade when only 10% of equipment was classed as ‘modern,’ to a level of 70% by 2020.

As a result of these commitments, the Russian defence budget has increased dramatically. Over the past year alone, Russia’s military spending is estimated by the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (SIPRI) to have increased by 4.8 %, and Russia is now spending a larger share of its GDP on the military than America. The Russian Government’s published 2014 military budget is reported as 2.49 trillion rubles (approximately US$69.3 billion) – the third largest in the world, following America and China. The official budget is set to rise to 3.03 trillion rubles (approximately US$83.7 billion) in 2015, and 3.36 trillion rubles (approximately US$93.9 billion) in 2016.

While Russia’s leadership has long harboured plans for military modernisation, the major catalyst for reform came with the 2008 war in Georgia. The Russian military victory confirmed the Kremlin’s belief that military power could be used in Russia’s neighbourhood, but it also demonstrated the serious shortcomings in the modernisation programme. Subsequently, the Kremlin has succeeded in pushing past the opposition of the conservative military bureaucracy to implement change.

The 2008 conflict in Georgia, and developments today in Ukraine, point to a wider process of militarisation underway in the countries of Eurasia, one driven primarily by local security concerns. Russia’s defence modernisation has been directed at these concerns as much as at a potential threat from NATO. At the core of these security challenges is a growing military competition focused on the Caspian Sea, the Black Sea and the Caucasus region.

With this competition in mind, all three South Caucasus countries and Kazakhstan have doubled their military spending since 2004, according to a recent report by SIPRI. Azerbaijan is the region’s big spender, with defence expenditure reaching $3.44 billion in 2013, up 493% since 2004. At the same time, Armenia spent $427 million in 2013, up 115% since 2004, while Georgia spent $443 million in 2013, up 230% since 2004; and Kazakhstan $2.8 billion, up 248% since 2004.

Regional conflict

The key drivers of the region’s galloping militarisation are, firstly, the various protracted Caucasian conflicts – Abkhazia and South Ossetia in Georgia, Nagorno-Karabakh, whose status is disputed between Azerbaijan and Armenia, and the North Caucasus, which has experienced near continuous conflict since the mid-1990s; and secondly, the rising geopolitical competition over the Caspian Sea and its enormous hydrocarbon resources.

The unresolved conflict over Nagorno-Karabakh is a particular source of tension. Following its defeat in the conflict over the disputed region in the early 1990s, and currently awash with its new-found hydrocarbon wealth, Azerbaijan has embarked on a military spending spree designed to break Armenia’s economy through an arms race. For its part, Armenia has sought to retain strategic parity with Azerbaijan via Russian military aid, and a long-term security relationship with Moscow, which includes the presence of a substantial Russian military base. In the summer of 2013, Russia announced plans to upgrade and modernise its military forces in Armenia.

Alongside the arms race over Nagorno-Karabakh, there is a growing naval build up in the hydrocarbon-rich but yet to be territorially delimited Caspian Sea. Here, not only have Russia, Kazakhstan and Azerbaijan announced plans to strengthen their navies, but Iran has also raised its defence spending in the region. In recent years, Iran has launched new ships, and Tehran has announced it will build the first submarine to operate in the Caspian Sea.

The growing militarisation of the Caucasus and the Caspian Sea is gradually spreading into neighbouring areas. While gaining influence over Kyiv has undoubtedly been a primary motivation behind Moscow’s actions towards Ukraine in recent months, asserting control over the Black Sea – and thereby over the Georgian seacoast and its hinterland across the South Caucasus – has also been a driving factor.

With the annexation of Crimea, Russia has gained full control over Sevastopol, the most important port on the Black Sea, as well as ensuring the virtual disappearance of the Ukrainian navy. Following the annexation, Admiral Viktor Chirkov, Commander-in-Chief of the Russian Navy, announced that the Russian Black Sea Fleet will be bolstered by the arrival of 30 new warships over the next six years, including a French-built Mistral amphibious assault ship; and that the port will be fully modernised.

A militarised diplomacy

A military approach is also taking a much more prominent role in Russia’s regional diplomacy as the Kremlin seeks to consolidate its dominance in Eurasia. This is being pursued within the Collective Security Treaty Organisation (CSTO), through large-scale military equipment transfers – more than $1 billion in weapons were allocated to Kyrgyzstan in 2013, and $200 million to Tajikistan – and the securing of overseas basing rights.

Arms deals have been linked to plans by Russia to strengthen its presence at the military base in Kant in Kyrgyzstan, following the recent departure of the US military from the nearby Manas airbase, from where they had been supporting operations in Afghanistan for a decade. Russia’s military basing agreement with Tajikistan was renewed at the end of 2013 – more than 7000 Russian troops will be stationed there up to 2042; underpinned by transfers of military equipment. This, together with the annexation of Crimea and the upgrading of the Russian base in Armenia, points to a new security dynamic in the region, one in which Russia’s military and security forces have positioned themselves as key factors influencing the stability (or otherwise) of its neighbours across much of the territory of the former Soviet Union.

Militarised societies

But the rise of military responses to regional challenges is not the only aspect of militarisation underway in Eurasia. The civil societies that have emerged in the region over the past 25 years, and which have played a central role in moving the countries of the region away from the rigid state-society relations of the Soviet era, are under assault as never before, as the region’s ruling elites seek to strengthen their control.

During President Putin’s first term, an effort was made to rebuild some of the practices that served to militarise Soviet society. For example, military training was reintroduced into Russian schools and there was a rising stress on patriotic education. But efforts to promote a re-militarisation of society did not resonate with the population. Dislike of the draft and a rising awareness of the systematic and often fatal hazing (dedovshchina) in the Russian military – often highlighted by civil society organisations such as the Committee of Soldiers Mothers – ensured that the Kremlin’s initiatives found little popular support.

Today, the Kremlin has found a new way to advance its domestic agenda of re-militarising society, namely by generating enormous domestic support for actions taken to enhance Russia’s external strength, and by creating a new social contract based upon the government’s promise to return Russia to the status of a ‘great power.’

The large scale popular support for policies to rebuild Russia’s central role in Eurasia – notably Russia’s right to use force externally, an expansionist view of Russian territory, and support for the annexation of Crimea – has been charted by the Levada Center, the Russian polling organisation; and there are record high levels of support for President Putin whenever he advances such goals. A key tool to help build support for such direct action is a carefully orchestrated media campaign designed to expose the Russian population to stark black and white narratives of military and extremist threats against Russia and ethnic Russians at home and abroad – nowhere more than Ukraine.

In this febrile climate, the Kremlin is free to pursue its foreign policy goals, and domestically it is able to clamp down on annoying dissenting voices. Russian authorities are able to move against civil society groups and opposition organisations under the guise of strengthening national security against ‘foreign agents.’

But such developments are not limited to Russia. Azerbaijan’s massive defence build-up is underpinned by similar domestic policies. Armenia and Armenians are continually portrayed in the state media as an almost existential threat to the country, a message also hammered home in the nation’s schools. At the same time, the Azeri Government has moved against independent journalists, human rights activists and NGOs, which might challenge the official security narrative justifying the need for this military build-up. A similar situation prevails in Armenia. In the Caucasus, whole generations are being raised to view neighbouring countries and societies as military threats that can only be countered through military responses.

A comprehensive regional approach

Nearly 25 years after the collapse of the Soviet Union, a new, highly militarised climate is being created that threatens peace amongst the Eurasian countries, and is substantially changing societies there. At its simplest, the change can be seen in the rising defence expenditures and the modernisation of armed forces across the region. But behind these trends are deep-seated political and social developments. Building on the popular support for security approaches to resolving issues with neighbouring countries, the states of the region are looking to roll back the liberal reforms of the past two decades, and to re-militarise state-society relations.

In these conditions, a wholly security-focused response to the Ukraine crisis by the ‘transatlantic community’ risks further entrenching hardliners in Moscow, and reinforcing the dangerous trends towards militarisation. At the same time, a narrow diplomatic approach focused only on Ukraine will not address the broader drift towards militarism in the region. In seeking a response to the Ukraine conflict and to Eurasia’s growing instability, the ‘Western community’ needs to craft a comprehensive regional approach that looks to address the sources of militarism. This will involve increased efforts to find peaceful solutions to Eurasia’s protracted conflicts, and the enmity that has built up around them. It will also require the establishment of a renewed security dialogue between Russia, its allies and the ‘transatlantic community’ to counter perceptions of insecurity and threats in the region, notably in the Caucasus and Caspian regions. Moreover, countries such as Britain might like to reconsider their arms deals with countries such as Russia, which can only further exacerbate instability. Such measures just might help slow down the galloping militarisation of Euraisa.

Article also appeared at opendemocracy.net/od-russia/neil-melvin/galloping-militarisation-of-eurasia bearing the following notice:

This article is published under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 licence. If you have any queries about republishing please contact us. Please check individual images for licensing details.

This article is published under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 licence. If you have any queries about republishing please contact us. Please check individual images for licensing details.