Russian money laundering: how does it work?

(opendemocracy.net – April 8, 2013 – Pavel Usanov)

Pavel Usanov is head of the Hayek Institute for Economy and Law in St. Petersburg and Reader at the Higher School of Economics.

Cyprus’s monetary crisis has drawn international attention to the island’s role as a tax haven and money laundry for Russia’s rich. Meanwhile, Putin has announced a crackdown at home which Pavel Usanov believes is doomed to failure, given the all-pervasive corruption of life in Russia.

In the USSR there were very few official millionaires, and most of them were film actors and sports stars who earned enormous fees abroad. There were many more unofficial millionaires, but they were obliged to convert ill-gotten gains into legal income using money laundering schemes: in the cult 1968 film comedy ‘The Diamond Arm’, for example, this involved burying contraband gemstones in the ground and then ‘discovering’ them again, since the finders of treasure trove were entitled to part of its value.

Times have changed, and Russia is third in the global billionaire league (after the USA and China), with Moscow having more billionaire residents than any other city in the world. However, in a recent interview with the ‘Vedomosti’ newspaper, Sergei Ignatyev, outgoing head of Russia’s Central Bank (CB), revealed that money laundering schemes are as widespread as ever. According to Ignatyev, $49 billion (£32 bn) was lost to the economy in 2012 in this way: ‘this could include payments for drugs or other goods which may not be legally imported into Russia’, and he sees an all out war on tax evasion and money laundering as a priority for his successor Elvira Nabiullina.

Ignatyev also told Vedomosti that in all other respects the Central Bank was doing a good job: its head evidently felt the need to create the image of an ‘enemy’ that was spoiling the otherwise perfect picture so carefully put together by the regulator. Apparently, all Russia’s financial problems boil down to people breaking the law; the law itself and other regulatory measures are perfectly fit for purpose and guarantee continued economic growth. Ignatyev considers, for example, that the CB was responsible for steering the correct monetary policy line during the financial crisis of 2008-9.

‘According to Ignatyev, $49 billion (£32 bn) was lost to the economy in 2012 in this way, and he sees an all out crackdown on tax evasion and money laundering as a priority for his successor.’

But let us not forget that the bank lost an enormous amount of money by bailing out the medium sized Mezhprombank (which has since gone into liquidation) and by artificially stimulating credit growth in 2008-9, when banks were forced to increase their credit portfolios every quarter despite a lack of sound borrowers, so producing new unsafe investments which will come to light in a future crisis. But all that, according to the bank’s outgoing head, is unimportant, and the main thing is to defeat the chosen ‘enemy’ tax evasion by business. According to Ignatyev, the exchequer loses 450-600 billion roubles (£9-12 bn) a year in this way, and 11% of businesses pay no tax at all. Since 2004 Russia has in fact had a special government agency, ‘Rosfinmonitoring’, charged with combatting money laundering, but after nine years its lack of progress evidently demands that its function be handed over the megaregulator that is the Central Bank.

I, however, believe that this is a misreading of the situation, and that there is another reason for the rise of Russia’s shadow economy.

How does money laundering work?

The aim of money laundering is to legalise money acquired by illegal means. This can be achieved in a number of ways: fictitious transactions, often involving fake documents; the deposit of cash in bank accounts or using ATMs; the use of offshore accounts; the withdrawal of cash for illegal activities and so on.

‘Why should a crackdown on money laundering be so crucial now? One reason is probably that even with the rise in gas and oil prices, the government can’t meet its financial commitments from existing income streams. And a campaign against the grey economy is also a potential source of extra income.’

The aim of the laundering is clear to allow the owner of the money to use it without worrying about the authorities asking questions. It is worth mentioning that when Rosfinmonitoring was set up in 2004 financial analysts believed that there was little need of money laundering in Russia, because of the low incidence of non-cash operations coupled with the fact that any service could be paid for in cash. The situation has however changed radically in the last ten years, with the rapid growth of non-cash transactions among all sectors of the public. The Central Bank’s stated position is that illegal earnings in Russia arise from drug trafficking and as a result of crime. For some reason it does not include in its list income generated through the so-called ‘grey’ economy, but that doesn’t mean that all such earnings are crime related; some are completely legal.

Why should an anti-money laundering initiative be so crucial now? One reason is probably that even with the rise in gas and oil prices, the government can’t meet its financial commitments from existing income streams. There is active discussion of ways of making up this shortfall and of means of raising finance to complete planned projects. And a campaign against the grey economy is also a potential source of extra income.

Here, it is true, one aspect of cause and effect is not being taken into account. The tax burden on Russian business has been rising significantly over the last few years, especially in 2011, when the employers’ social insurance contribution for small businesses was tripled (it has recently been increased yet again). The investment environment is also not good; the World Bank’s ‘ease of doing business’ index puts Russia at No.112 out of 185 countries. As a result there is a drain of capital and a retreat into the ‘shadow’ economy which is extending to wages and salaries. The rising cost of corruption that has followed the expansion of the state has also had a negative effect on the quality of the institutional environment. The question arises of how business can go on existing in Russia at all. One answer is to go into the ‘shadows’, and minimise your tax bill.

The Cyprus option …

One of the most popular ways of minimising your taxes in Russia is to take your money abroad to an offshore tax haven. Low taxation and a high level of protection of property rights attract financial institutions from all over the world to so-called free economic zones, and although Cyprus was formally struck off the Russian offshore list on 1st January 2013, it is still being used as a tax shelter. According to the head of its central bank, Cyprus holds deposits from Russian citizens totalling €5-10 billion (£4-8bn) a third of all deposits on an island with no tax on dividends or stock transactions, a very low rate of corporation tax and agreements with every country in the world not to levy double taxation (Moody’s, the US credit rating agency, puts the value of Russian deposits in banks and loans to Cypriot companies much higher, at $70 billion (£60bn), or about 4 percent of Russia’s GDP). The EU’s attempt to expropriate depositors’ cash through a ‘stabilisation tax’ triggered an extreme reaction from the Russian government, which has led many analysts to suspect that our rulers have a personal financial interest in the island.

‘According to the head of its central bank, Cyprus holds deposits from Russian citizens totalling €5-10 billion (£4-8bn) a third of all deposits on the island. Moody’s, the US credit rating agency, puts the value of Russian deposits and loans to Cypriot companies much higher, at $70 billion (£60bn), or about 4 percent of Russia’s GDP.’

Everyone imagines that all the Russian money in Cyprian bank vaults derives from criminal activity, but this has never been proved. To say that all the money deposited by Russians on Cyprus is connected with crime is the same as saying that all Russian money is dodgy and that all Russians are crooks. Offshore tax havens are a way of protecting one’s capital, although these days many governments regard this as a crime in itself. It is after all easier to take from those whose property rights are limited and those who have no right to protect these rights, and move the money to places where property rights are protected.

… but you can also do it at home

Money laundering facilities are, however, not just available to billionaires, and not only in overseas tax havens. There are plenty of opportunities for it in Russia itself. One widespread way of laundering money is to use a bank to transfer, for a fee, a sum of money from a cash to a non-cash form, or vice versa, in such a way as to disguise its origins. German Gref, the head of Russia’s Sberbank (Savings Bank) recently estimated that 20% of Russian banks act as ‘launderies’, and called for their licences to be revoked. Gref’s interest here is of course not entirely altruistic: his bank already accounts for 50% of the market, and the removal of other similar financial institutions would lead to its further expansion.

Credit cards can also be used to launder unofficial earnings. Money can be paid into an ATM or a bank, and if it needs to stay below the radar, it can be credited to a card account. If it’s only a small sum there won’t be any fee involved; if large, depositing and cashing services will cost between 3-10% of the amount. In Russia there are more than 3000 organisations offering these services, and only part of the fee involved goes to them: the rest goes to officials as protection money.

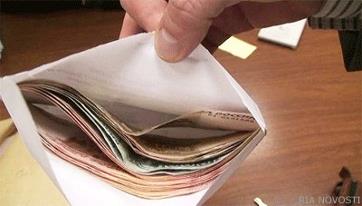

From back in the 90s scams involving fictitious contracts and other documents have also been very popular. A business is paid for producing goods that either don’t exist or are worth much less than stated on its invoice, and the money is perfectly legal even if the goods are fictitious. For example, a high level official organises a contract for a company and is owed a kickback. He is given an envelope full of cash, which he needs to launder. The money is distributed to various third parties and comes back to the company through various fictitious operations, and the official is then paid a perfectly legal consultancy fee. Such high ranking officials are often behind illegal business, pocketing illegal cash.

What goes around, comes around

A high level official organises a contract for a company and is owed a kickback. He is given an envelope full of cash, which he needs to launder. The money is distributed to various third parties, returns to the company via various fictitious operations, and the official receives it again in the guise of a perfectly legal consultancy fee.’

2012 saw the release of Mikhail Segal’s film ‘Short Stories’, which consists of four narratives about life in Russia today. One of these, entitled ‘What goes around, comes around’, has corruption as its theme, and is an excellent illustration of how this works. At the start of the episode, a driver is trying to get a fake MOT certificate for his car, which will cost him 10,000 roubles (£200). The man who organises the certificate takes the cash to the passport office and uses it to jump the queue for an international passport. The manager of the passport office takes the money to a professor who can help his daughter get a university place. The professor in turn takes it to a doctor to get an operation for his wife, and the doctor then hands it over at the army recruitment office so that his son can avoid conscription. The officer in charge at the recruitment office gives the money to a builder who has promised to allocate him a council flat, and the process finishes at the top of the social ladder when the regional governor gives the builder a building plot in return for the council housing block. The governor goes on to meet the President himself, and keeps his job after guaranteeing the ‘right’ results in the regional elections, as well as promising to fight corruption. The story finishes with the driver coming to pick up his fake MOT and is amazed when he actually gets it. ‘What about all this stuff on TV?’ he asks. ‘The government’s cracking down on corruption. How did you wangle it?’ The reply? ‘Well, why do you think it used to cost 10,000, and it’s gone up to 15,000 now?’

‘The government’s supposed crackdown on corruption has not reduced corruption, because there has been no reduction in demand. And the same goes for the anti-money laundering campaign: the only result can be inflation in the cost of dodgy deals and more cash lining the bureaucrats’ pockets.’

In other words, the only result of the government’s crackdown on corruption has been 50% inflation in the cost of dodgy deals. There has been no reduction in corruption, because there has been no reduction in demand. And the same goes for the anti-money laundering campaign: the only result can be a similar price inflation and more cash lining the bureaucrats’ pockets. This greying of the economy could also be itself a result of high business taxation: when this is the only way to preserve jobs and capital, paying all your taxes could mean your business going bust and your staff losing their jobs.

The real reason for the rising rate of money laundering is increased taxation and an expanding bureaucracy, and not the innate criminal tendencies of the Russian public. The continuing growth of the government sector will mean an increasing squeeze on the private sector, when the growing appetites of the officials can no longer be satisfied by business owners bent under the weight of taxation and bureaucracy. If the policy of increasing state control of the economy continues, money laundering will always be a profitable business.

Article also appeared at http://www.opendemocracy.net/od-russia/pavel-usanov/russian-money-laundering-how-does-it-work bearing the following notice:

This article is published under a Creative Commons licence. If you have any queries about republishing please contact us. Please check individual images for licensing details.

This article is published under a Creative Commons licence. If you have any queries about republishing please contact us. Please check individual images for licensing details.