Russia Retaliates Against U.S. Space Program in Response to Sanctions

(Moscow Times – themoscowtimes.com – Matthew Bodner – May 14, 2014) Two weeks after warning the U.S. that sanctions on Russia’s space industry would have a “boomerang” effect, Deputy Prime Ministry Dmitry Rogozin announced that Russia was rejecting a NASA proposal to extend cooperation on the International Space Station and would limit exports of its rocket engines to the U.S.

Rogozin said that Russia would not accept a NASA proposal to extend the life of the International Space Station, or ISS beyond 2020, “After 2020, we would like to divert these funds [used for ISS] to more promising space projects,” he said, Interfax reported on Tuesday.

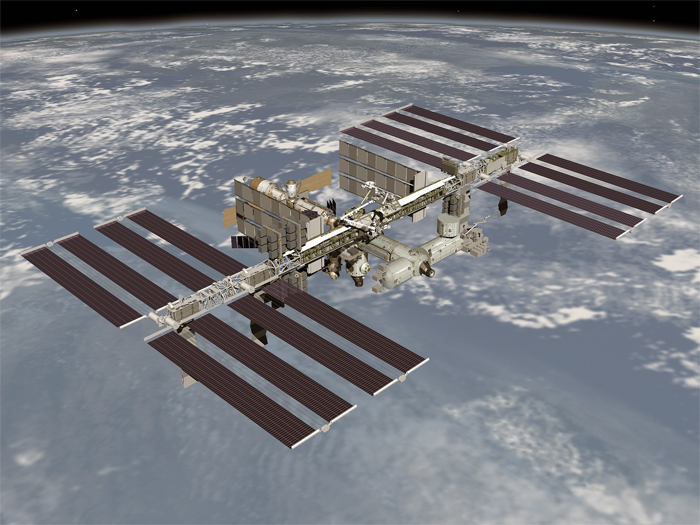

For 20 years, the U.S. and Russia have quietly cooperated in space exploration. The ISS program, a $100 billion project involving 15 nations, has been the hallmark of these efforts, remaining above the fray of the political ups-and- downs of the larger U.S.-Russia bilateral relationship.

Even when an order was passed down the ranks of NASA personnel in April to cease all contact with Russian space officials – with the important exception of those activities required to maintain operations aboard ISS – civil space cooperation seemed to be unharmed. NASA administrator Charles Bolden quickly assured the space community that nothing had changed, and that work would continue unabated.

In an interview with Vedomosti later in April, Roscosmos chief Oleg Ostapenko backed up Bolden’s assertion, saying that Roscosmos had not received any notifications from their NASA counterparts that cooperation was being suspended.

But it now appears that this privileged state of affairs is no more. Rogozin said that Russia was “seriously concerned” about continuing a relationship with an unreliable partner, such as the U.S., and that Roscosmos has been instructed “to intensify work with our partners in the Asia-Pacific region who are looking for interesting near-earth and deep-space projects.”

Roscosmos chief Oleg Ostapenko also said in the Vedomosti interview that Moscow was pursuing closer cooperation with China – the latest player in space exploration.

In the meantime, Rogozin said that “we understand that the International Space Station is fragile in the literal and figurative sense,” and would therefore “act very pragmatically and not put obstacles in the way of work on the ISS.”

These developments comes at an awkward time, as the U.S is currently without its own vehicle for transporting astronauts to the space station, and must rely on the Russian Soyuz for rides. Both space agencies are currently preparing for the return of an ISS crew on Tuesday night, followed by the launch of their replacements on May 28.

The decision not to continue work on ISS past 2020 also raises questions concerning a new Russian addition to the space stati on – the Nauka science module, which was supposed to launch in 2007, but now is not going to be delivered until 2017.

This consideration places another one of Rogozin’s statements, that the Russian portion of the space station was capable of functioning without the U.S. portion, in valuable context.

In addition to intergovernmental space cooperation aboard the ISS, Rogozin made a number of statements that have direct ramifications for U.S.-Russia commercial space cooperation – which has already been subject to the ongoing tit-for-tat sanctions battle between Washington and Moscow.

In a move that closely mirrors last month’s U.S. State Department restriction of high-technology, dual-use exports to Russia that might be of assistance to the Russian military, Rogozin told reporters that Russia would limit the exports of its valuable rocket engines to the U.S.

Ostapenko on Tuesday clarified the terms of the Russian reprisal, saying that Russia w as prepared to continue supplying the engines, “but on one condition, that they will not be used to launch military satellites.”

One of the engines, the RD-180, is used to power the first stage of the Atlas V rocket – currently the only vehicle in the U.S. launch fleet certified to deliver U.S. national security payloads to orbit. United Launch Alliance, or ULA, the company that produces the Atlas V, currently has two years worth of the engines stockpiled domestically.