NEWSLINK: Russia’s Syria Support said to be a Losing Proposition

[Russia’s Syria Support Said to be a Losing Proposition – Vedomosti – Vladislav Inozemtsev, doctor of economic sciences, director of the Center for Study of the Post-Industrial Society – December 24, 2012 – no accessible link]

Vladislav Inozemtsev writes in Vedomosti on Russia’s Syria policy, also focusing strongly on economic factors such as oil, gas and Syrian debt. At the same time, he suggest current Russian leaders are an anachronism, hearkening back to old Soviet styles and preferences when it comes to foreign strongmen.

He argues that Russia continuies to be dependent on energy exports to fuel its economic position, yet has alienated key parties in the energy sphere, such as other oil producers:

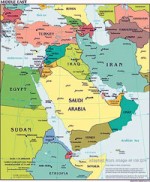

Russia is an “energy superpower”. At least, this is what Vladimir Putin said on 23 December 2005 at a session of the Security Council. The country’s dependence on exports of energy sources has since that time only increased. It is prudent, therefore, to coordinate policy with the trendsetters on the energy market.

In the sphere of oil supplies these are, of course, OPEC and its leader–Saudi Arabia. OPEC currently produces 29.3-29.7 million barrels of oil a day out of a world production of 83.2-83.5 million barrels; Russia, up to 10.3 million barrels. Were Russia an OPEC member, it would control one-half of global production and would be a more effective regulator of price policy, which under the conditions of a possible crisis is not immaterial.

But our relations are far from ideal: as recently as 14 November the aircraft of Sergey Lavrov en route to a meeting of foreign ministers of the Gulf Cooperation Council was not allowed to land at the main airport of the Saudi capital of Riyadh, and the head of Russian diplomacy himself left before the conclusion of the summit since he had not been given a hearing. Perhaps we should not in this situation be pushing in the direction of such aggravation?

Gas is also significant to Russian economic interests, with Qatar a key competitor grabbing market share, in part due to what Inozemtsev calls ineptitude by Gazprom:

Aside from oil, we are interested in gas also, and the lead player in this market is Qatar. From 1990 through 2011 it increased production from 6.3 billion to 146 billion cubic meters a year; if this trend continues, the country will be the world’s biggest gas exporter as soon as 2021 (calculated from BP Statistical Review of World Energy 2012). Moreover, Qatar even today controls 31.3% of the global liquefied natural gas market (see The LNG Industry 2011, Paris: International Group of LNG Importers, 2012, p 4), which is far more flexible than the pipeline deliveries market. It is Qatar that has methodically taken more than 80% of the share that Russia, owing to Gazprom’s inept pricing policy, lost on the European market between 2005 and 2011. Why not develop bilateral ties and strengthen cooperation, exchanging political for economic concessions. But not a bit of it.

Inozemtsev raises concerns over whether Russian diplomacy is undermining Russian economic interests, with leadership skewed in its perspective by Soviet influences:

I would like to inquire: is this diplomacy not a direct wrecking of Russia’s economic interests? And what are we achieving by such strange steps?

The answer is there for all to see. It consists of the inexplicably good disposition of our political elite toward dictator outcasts of the Muammar Al-Qadhafi and Bashar al-Assad type. Our diplomats, admirers of Leonid Brezhnev and Andrey Gromyko, are very fond of “leaders” left over from the times of these statesmen and even of their offspring.

Inozemtsev casts Russo-Syria relations as a potpourri of Russian financial losses, unpaid military transfers and would-be geostrategic interests that do not seem to be manifested:

Let’s take Syria. From the perspective of the economist, Syria is our long-standing debtor. Following two debt write-offs by 2005, it owed Russia $13.5 billion. We then signed with it a treaty, according to which we forgave 73% of the debt. Why? Syria promised to repay the balance over 10 years–not in money but in supplies of its goods. Where are they and how much of them has arrived in seven of the 10 past years? Following this “breakthrough,” cooperation in supplies of weapons was stepped up (the package has now amounted to $3.5 billion and includes missile systems, aircraft, and air-defense systems). No more than 20% of all this has been paid for in hard cash. Once again, why? Whose interests have been engaged in these “arrangements”? It is believed that in Syria Russia has strategic interests based on the Black Sea Fleet’s use of the base in Tartus–but what operations does the fleet conduct in the Mediterranean? And when, finally, was the last time it was there?

In addition to Russia backing Syria, Inozemtsev observes the Russian government of promoting terrorist organization Hamas, with Hamas actually threatening the lives of Russian citizens abroad:

… Russia has one further friend in the region — the Hamas terrorist movement. Russia prevented in the United Nations the adoption of a resolution which would have said that it was Hamas that was the first to begin the rocketing of Israeli territory. An Israel in which hundreds of thousands of citizens with Russian passports live. When Georgia attacked South Ossetia, which is populated by people that had dubiously purchased our passports, we raised an army. When the enemy shells a country that is now home to thousands of Great Patriotic War veterans, we do not say a word. What highest interests are engaged this time?

Iran joins the cast of characters courting Russian favor, even while representing instability and a potential nuclear threat, as well as one brand of Islamist fanaticism:

Further, we love Iran. Iran, which is not a conduit of our interests and which counterposes itself to the Arab world, not to mention the West. Which is close to the building of nuclear weapons capable of destabilizing the situation in the region. Why? What does Iran have, other than hatred of America, that is pushing us into an alliance with it? Or have we opted for religious fundamentalism, of whatever interpretation, as a model for which we are fatally attracted?

Inozemtsev predicts that Syrian opposition will, in fact, topple Assad in the end, and he expresses concern that Russian policies across broad fronts are undermining Russian interests, resulting in Syria’s failure to pay its debts, and antagonism from energy competitors, the West and Israel, without bearing any fruit, while Iran stokes growing instability, nuclear proliferation and increased chances for military conflict:

… as a result of the defense of the hopelessly defeated al-Assad, Russia has counterposed itself to the lead players of this energy market, on which our well-being depends. Emboldening Iran and Hamas, we are not even converting them into our allies (although thank God!). And relations with Israel are hardly likely to improve in the light of recent events. [Meanwhile] the Europeans are establishing relations with the future authorities of Syria … [the United States continues to address] the Palestinian-Israeli conflict for weeks [yet] Russian diplomacy has been absent from the region.

… events are unfolding according to scenarios other than those to the liking of Smolenskaya Ploshchad. So let’s attempt to take a look at how they will possibly move. The Syrian insurgents will soon finish off the al-Assad regime. The Russian debts will be forgotten, the contracts will be annulled. Iran, having lost its ally, will increase assistance to Hamas and accelerate its program of the building of an atomic bomb. Israel will cut off the oxygen to Gaza and, perhaps, mount a preventive attack on Iran’s nuclear facilities. Tehran will respond. The United States will intervene. The result will be a situation similar to the situation in Iraq after 1991–Iran will not be occupied but it will cease to be a wholly independent country. Russia will derive no benefit from all this–as after the war in Iraq in 2003. We will remain in the memory of the regional leaders as a country which for five years supported all losers, whichever it could find, without exception.

Inozemtsev points out that, in terms of actual profits and global security enhancements, there could be net benefits from a Russian change in policy, aimed at improving ties, for example, with Gulf Arabs, Europe and Israel:

… has the Russian leadership weighed … [a] scenario in which we are prepared to surrender the “Damascus inmate” in exchange for a normalization of relations with the Saudis and Qataris? To reserve for ourselves a seat at the table at which Syria’s future is decided — and to obtain, finally, from this erstwhile friendly country if only some of the old debts? After all, were we to restore to ourselves if only 1% of the European gas market, the proceeds would exceed the amount of earnings from the sale of weapons to Syria for the coming decade! Were we to support Israel, there would be fewer terrorists and gunmen in the world, and those left would comport themselves somewhat more quietly. But I will go even further and ask: why should we be opposed to Israel and the United States mounting attacks on Iran? How would such a conflict be disadvantageous to us? Remember under what circumstances in 2002-2004 the price of oil grew from $22 to almost $50 a barrel? This was the price of the smashing of Saddam Husayn. What would it be following a war in the Strait of Hormuz? $170 a barrel? Or all of $200? “We know the consequences of outside armed intervention not sanctioned by the UN Security Council in the aff airs of other states,” Sergey Lavrov gravely pronounced on 1 December at the anniversary assembly of the Foreign and Defense Policy Council. We do indeed. Our authorities have for more than 10 years now been living parasitically on these “consequences,” having no problems with the budget.