How Big Is Russia’s Win in Syria?

(Russia Matters – russiamatters.org – Michael Sharnoff – November 6, 2019)

Dr. Michael Sharnoff is an associate professor at the National Defense University’s Near East South Asia Center for Strategic Studies in Washington, D.C. He is the author of “Nasser’s Peace: Egypt’s Response to the 1967 War with Israel.” The opinions, conclusions and recommendations expressed or implied within are solely those of the author and do not necessarily represent the views of the U.S. Department of Defense or any other agency of the federal government.

he Trump administration’s Oct. 13 announcement of a withdrawal of U.S. troops from northern Syria created a media storm, in which multiple editors, journalists and op-ed contributors declared the move to be a “win,” “victory” and “gift” for Russia and its leader Vladimir Putin. In my view, however, while Putin’s Russia has indeed collected a number of short-term dividends from the announced withdrawal, this “victory” is far from winning Moscow the war in Syria.

U.S. Withdraws From Syria … or Not

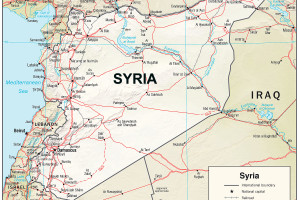

The United States announced on Oct. 13 that it will withdraw about 1,000 troops from northern Syria, leaving the U.S.-backed and Kurdish-led Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF) to fend for themselves. U.S. President Donald Trump’s decision caught some policymakers by surprise, and many have argued that the U.S. has betrayed its Kurdish partners, even though Trump has consistently articulated a desire to disengage from Syria. Trump’s critics were quick to point out that the withdrawal constituted a gain for Russia’s role in this Arab country. It also emboldened Turkey to make greater inroads into northern Syria under a pretext of fighting Kurds affiliated with the SDF, which was instrumental in rolling back the Islamic State (IS)’s territorial gains in Syria and putting ten thousand male IS members in detention tents. Less than two weeks after the announced withdrawal, however, the U.S. military deployed new forces to Syria to secure oil fields in the eastern part of country so they would not fall into the hands of IS fighters. Then, on Nov. 1, Trump expanded this mission to protect lands controlled by Syrian Kurdish fighters that extend from Deir el-Zour to al-Hassakeh. This new deployment reportedly brought the number of U.S. servicemen in Syria to some 900, which is only 100 less than before the Oct. 13 announcement. The new deployment makes the U.S. more prepared to prevent the resurgence of the Islamic State, whose defeat remains one of the top strategic priorities for Washington, along with countering Iranian influence in the region. As air power alone cannot prevent an IS comeback, ground forces are critical for the success of that mission, especially with SDF fighters distracted by the Turkish invasion. The U.S. re-deployment also helps to ensure that the U.S. has some say in the outcome of the broader Syrian conflict even as Russia’s impact on that outcome increases.

U.S. and Russian Interests vis-à-vis Syria: Some Convergence?

Russian President Vladimir Putin has acknowledged, alongside Trump, that eliminating IS is a high-priority interest for his country, if only because of the thousands of Russian nationals in the ranks of this terrorist organization, fueling the Kremlin’s fears that they may return home to wage a terrorist campaign in Russia. The need to keep IS down is also consistent with Russia’s steadfast support of its ally, Syrian President Bashar al-Assad.

It could also be argued that, in addition to agreeing on the need to keep IS down and Syria stable enough to prevent it from becoming a terrorist haven, the U.S. and Russia are also both interested in countering the Iranian influence in Syria. As stated above, countering Iran is one of Washington’s strategic priorities as outlined in the 2017 National Security Strategy. As for Moscow, although Russia and Iran both support the regime in Syria, they are strategic competitors and not natural allies. Indeed, both countries compete for contracts to rebuild Syria and strengthen their influence. As one analyst observed, “While Russia seeks to rebuild the state and its core structures and to recentralize state authority over all arms of power, Iran seeks to infiltrate and embed itself within the state, while simultaneously building deep-rooted parallel arms of power under its direct control.”

However, the U.S. and Russia disagree profoundly over how to counter Iranian influence in Syria. In fact, potential for any strategic U.S.-Russian cooperation on Syria between the two appears slim for a number of reasons.

Historical Precedents and Realities in Syria

Russia is an adversary of the United States and competes to supplant U.S. influence not just in Syria but throughout the region. It wants the United States out of Syria and has blocked U.N. Security Council Resolutions regarding the use of chemical weapons and other war crimes perpetrated by Assad’s regime in defiance of the West. Putin wants to ensure that his country has a dominant role in Syria’s future and has declared that all foreign militaries—those that are not invited guests of the legitimate government—must leave Syria. On Oct. 22, while standing next to Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, Putin said, “Syria should be free from illegal foreign military presence,” making it clear that the United States and Turkey’s military presence in Syria must end.

Syria is one of the few Middle Eastern countries that has never had close relations with the United States. Washington has never truly viewed Syria as a national strategic interest, and as a consequence, its ability to exert influence has always been constrained. In contrast, Syria has been a close Russian ally since the 1950s, when both countries came together over the shared goal of blocking U.S. efforts to conclude separate peace treaties between Israel and the Arab states. Moscow viewed Damascus, with its warm-water ports at Tartus and Latakia, as a potential foothold in the Eastern Mediterranean. After Nasser’s Egypt, Syria became the largest recipient of Soviet aid in the Middle East. In exchange, the Syrians received Russian military equipment, which allowed them to pursue strategic parity with Israel. Russia’s policy objectives have been clear and concise since the beginning of the Syrian Civil War in 2011: support and defend the Assad government while also eliminating as many Russian nationals in the ranks of anti-Assad forces as possible to prevent them from returning to Russia with arms. To achieve these objectives, Moscow deployed its military to Syria in 2015 in a move that the Russian Orthodox Church sanctioned as necessary to defend Russia from terrorism. Russian forces then proceeded to help the Assad regime ruthlessly fight the rebel opposition, be they Salafi-jihadi terrorists like Islamic State and al-Qaida, the Free Syrian Army or civilians. Russia’s military intervention in 2015 turned the tide, helping to not only prop up Assad’s regime but to also eliminate many Russian nationals in the anti-Assad forces. Russia has gained short-term dividends by successfully portraying a narrative that it stands by its friends and allies—no matter how ruthless, and it has denounced the United States as an untrustworthy ally who will abandon its friends. Russia’s ability to exploit this sentiment has become more acute after the recent U.S. treatment of its Kurdish partners in Syria. As a consequence, countries such as Egypt, Iraq, Saudi Arabia and Jordan have recently sought to expand economic and security cooperation with Moscow. Today, with the U.S. footprint in Syria diminished, Russia is working to further expand its influence in Syria and the region while curbing U.S. influence.

Conclusion

Assad has survived due to Russian and Iranian support, but he rules over a fractured country that will take decades to rebuild. Syria is a failing state and a humanitarian catastrophe with over 500,000 Syrians killed and 13 million displaced. The U.N. estimates restructuring efforts will cost over $300 billion. Moreover, Assad’s government does not exercise control over all of its territory. Pockets of political and gang violence persist. Neither Assad’s regime nor Russia nor Iran can fully tackle these challenges, either on their own or together, even if they were to somehow fully reconcile their interests. While Russia has clearly surpassed the United States in exerting influence in Syria, it must now at times cooperate with—and compete against—Iran and Turkey, the two other primary external actors in Syria. Russia will also have to contend with fundamental economic and security challenges. Does Russia have the capacity to prevent an IS resurgence? How will Russia curb Iranian influence in Syria? And does Moscow have the financial means to contribute toward Syria’s reconstruction? These critical issues will weigh heavily on the future stability and security of Syria. Russia has clearly benefited from the reduction of the U.S. presence in Syria, but it remains far from winning the Syrian war on its own terms.

Article also appeared, with different images, at russiamatters.org/analysis/how-big-russias-win-syria, with different images, bearing the notice: “© Russia Matters 2018 … This project has been made possible with support from Carnegie Corporation of New York,” with a footer heading entitled “Republication Guidelines” linking to: russiamatters.org/node/7406, which bears the notice, in part:

“If you would like to reprint one of these articles, a blog post written by RM staff, one of our infographics or a fact-check, we ask that you follow these guidelines:

- Include a prominent attribution to Russia Matters as the source and link back to the original at RussiaMatters.org.

- Retain the hyperlinks used in the original content.

- Do not change the meaning of the article in any way.

- Get an ok from us for non-substantive changes like partial reprints or headline rewrites and inform readers of any such modifications (e.g., This article first appeared on the Russia Matters website with the headline “Russian Election Interference in Trump’s Own Words”).

- Let us know about the reprint and send a link!

Please note that Russia Matters cannot grant permissions for third-party content, including articles, photographs and other materials not produced by our team.

Questions? Email us at RussiaMatters@hks.harvard.edu.”