Can the Biden Administration Get Russia Policy Right?

(Russia Matters – russiamatters.org – Thomas Graham – March 18, 2021)

In its first two months, the Biden administration has made two central planks of its Russia policy crystal clear: It has no interest in a reset, and Russia is not a priority. The sharp break with President Donald Trump’s aspirations was plainly intended as a message to both the American public and the Kremlin that the White House is under new, tougher management.

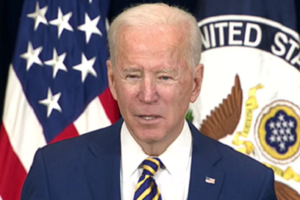

U.S. President Joe Biden’s first call to Russian President Vladimir Putin shortly after his inauguration was no indication of Russia’s place on his foreign policy agenda. The timing was dictated by the approaching expiration of the New START agreement on Feb. 5, the extension of which the new administration firmly believed was in America’s interest. More important, according to the White House, Biden used the call to raise issues of concern—Ukraine, the SolarWinds hack, alleged Russian bounties for killing American soldiers in Afghanistan, interference in the 2020 elections and the poisoning of Russian opposition leader Alexei Navalny—and to send an unvarnished message: The United States will resolutely counter Russian actions that harm it or its allies. To drive that point home, Biden reiterated it in his remarks at the State Department nine days later.

Action followed in early March, as the administration levied its first sanctions against Russia for the poisoning of Navalny, while promising further punitive measures in retaliation for the SolarWinds hack, electoral interference and the alleged bounties. Nevertheless, the administration insists it is not seeking to escalate tensions with Moscow. “We are seeking stability and predictability and areas of constructive work with Russia, where it is in our interest to do that,” a senior official explained. Russia meanwhile has promised a response to American sanctions, and also summoned its ambassador to the United States back to Moscow for urgent consultations after Biden publicly agreed Putin was a killer. But so far, hope for better relations has not completely vanished. The ambassador plans “to discuss ways to rectify Russia-U.S. ties that are in crisis,” while the Kremlin continues to stress that it is prepared to engage with the United States on the full range of issues whenever Washington is ready.

The Kremlin could be waiting for some time. Russia is no longer a priority for the United States. China is. The contrast in the administration’s handling of the two countries is striking. The Interim National Security Strategy Guidance, released on March 3, devotes considerable attention to China as a long-term strategic competitor, “potentially capable of combining its economic, diplomatic, military, and technological power to mount a sustained challenge to a stable and open international system”; it mentions Russia only in passing as a country determined to “play a disruptive role on the world stage.” U.S. Secretary of State Antony Blinken, in his maiden foreign policy speech the same day, listed China among the administration’s eight foreign policy priorities; he devoted no serious attention to Russia at all. Earlier, Biden appointed a senior official to the National Security Council staff to act as the “Asia czar” with a focus on China; there is still no permanent NSC staffer to oversee Russia policy, and a State Department, not a White House, official will likely oversee the administration’s Russia policy. Finally, Blinken and national security adviser Jake Sullivan met face-to-face with China’s top two diplomats on March 18 to discuss expectations for relations; no analogous meeting with Russian officials is on the horizon.

Contrary to past administrations’ calculi, Russia’s huge nuclear arsenal is not a sufficient reason for the Biden administration to make Russia a priority. To be sure, Biden agreed to extend the New START agreement and will seek a follow-on treaty with Russia, but tellingly his administration has not identified strategic stability as a priority. Biden is not tempted by President Barack Obama’s vision of a world without nuclear weapons, which animated his “reset” with Russia. Even Russia’s increasingly close strategic alignment with China has seemingly done nothing to raise its profile with the new administration. Indeed, no senior official has spoken of this alignment as a factor in internal deliberations. That suggests that the administration is likely to continue the practice of formulating China and Russia policy in separate silos. By ignoring the ways in which each country bolsters the other’s challenge to the United States and overlooking areas, such as strategic stability and climate change, where trilateral U.S.-Russia-China cooperation could yield outsized benefits, such an approach will undermine the effectiveness of policy toward each country.

Whether the administration’s initial posture toward Russia will hold as it formulates the details of its policy in coming months remains to be seen. As always, there will be surprises, and the administration will likely find itself compelled to engage more often with Russia than it anticipates or wants to. For, as was true for past administrations, Russia is a player on many issues the Biden administration will soon have to confront. Ending the “forever wars” in Afghanistan and Syria on satisfactory terms, as Biden has promised to do, will be impossible without Russia’s support. In Syria, Russia remains the dominant outside power. In Afghanistan, it has well-developed ties with the Taliban and powerful warlords who will determine whether a settlement can be reached that will allow the United States to leave with some dignity. That is why Blinken is pushing for a U.N.-hosted foreign ministers meeting on Afghanistan in the near future that will include Russia, along with China, India, Pakistan, Iran and the United States.

For similar reasons, the administration’s effort to rejoin the Iran nuclear deal, or negotiate a new one, will require engaging Russia, whose close relations with Iran proved pivotal to forging the original agreement. On climate change, another administration priority, Russia’s current two-year stint as chair of the Arctic Council and burgeoning presence in the High North guarantee a leading role in a region critical to the climate’s future. And if the administration wants to persuade China to engage on matters of strategic stability, something Beijing has adamantly resisted, it will need the help of the world’s other nuclear superpower.

At the same time, the administration will find that countering Russia’s aggressive conduct is not as straightforward a proposition as it has suggested. That effort will have to be balanced against other administration goals. Take Nord Stream 2, for example: Levying new sanctions under congressional pressure against European firms participating in the pipeline project, including those of key allies such as Germany, risks imperiling Biden’s stated priority of rebuilding transatlantic relations after four years of Trump’s destructive policies. Similarly, the promise to coordinate anti-Russian sanctions with the European Union will almost certainly lead to weaker measures than the administration might prefer, as member states are unlikely to reach a consensus in support of tougher ones.

More important, building a coalition to contain China could also lead to a less stringent anti-Russia policy. Punishing India for purchasing Russia’s advanced S-400 air defense system makes little sense while the administration is seeking to make it a partner in taming China. Risking an escalating cyber conflict with Russia over the SolarWinds hack, which would distract time and energy from the focus on China, is at best dubious. Such considerations could nudge the administration toward seeing the wisdom of making Russia and China policy in tandem, as Robert Legvold and I have advised elsewhere.

In the end, the administration might achieve what it has set out to do—no reset, no escalation in relations with Russia—but only because its actual policy, while still firm, will be less tough, and its engagement with Russia more frequent, than its rhetoric suggests. That would bring a welcome halt to the dangerous deterioration that relations have suffered during the past several years without compromising any vital interests. This stabilization would count as a major success for Biden, even if it is not now an avowed goal.

Article also appeared, at russiamatters.org/analysis/can-biden-administration-get-russia-policy-right, with different images, bearing the notice: “© Russia Matters 2018 … This project has been made possible with support from Carnegie Corporation of New York,” with a footer heading entitled “Republication Guidelines” linking to: russiamatters.org/node/7406, which bears the notice, in part:

“If you would like to reprint one of these articles, a blog post written by RM staff, one of our infographics or a fact-check, we ask that you follow these guidelines:

- Include a prominent attribution to Russia Matters as the source and link back to the original at RussiaMatters.org.

- Retain the hyperlinks used in the original content.

- Do not change the meaning of the article in any way.

- Get an ok from us for non-substantive changes like partial reprints or headline rewrites and inform readers of any such modifications (e.g., This article first appeared on the Russia Matters website with the headline “Russian Election Interference in Trump’s Own Words”).

- Let us know about the reprint and send a link!

Please note that Russia Matters cannot grant permissions for third-party content, including articles, photographs and other materials not produced by our team.

Questions? Email us at RussiaMatters@hks.harvard.edu.”