“Crises in the Second Nuclear Age” – Stephen J. Cimbala, Paul Bracken

Subject: Crises in the Second Nuclear Age

Date: Fri, 21 Apr 2017

From: STEPHEN CIMBALA <sjc2@psu.edu>

Crises in the Second Nuclear Age

By Stephen J. Cimbala and Paul Bracken

Stephen J. Cimbala is Professor of Political Science at Penn State Brandywine. Paul Bracken is Professor of Management and Professor of Political Science at Yale University.

Nuclear weapons coincided with the Cold War. The United States and other powers had to navigate the dangers of nuclear war while still protecting their respective national interests. Only in retrospect does this seem like a success story. For those of us who lived through it, the Cold War was seen as very dangerous, and, in selected moments, presenting of apocalyptic threats to civilization. The end of the Cold War and the demise of the Soviet Union seemed to anticipate a historical turning point that might rebottle the nuclear genie and reboot international politics away from dependency on nuclear threat systems.

Instead of acquiring pariah status, nuclear weapons have remained in the arsenals of existing nuclear powers, and other states are interested in acquiring them. In addition, most of the nine current nuclear weapons states are all engaged in, or planning for, extensive modernizations of their nuclear arsenals and-or weapons establishments.

Instead of acquiring pariah status, nuclear weapons have remained in the arsenals of existing nuclear powers, and other states are interested in acquiring them. In addition, most of the nine current nuclear weapons states are all engaged in, or planning for, extensive modernizations of their nuclear arsenals and-or weapons establishments.

President Barack Obama called in 2009 for eventual nuclear abolition in 2009, but his own defense planning guidance stated that, unless and until nuclear weapons were abolished, the United States must maintain a nuclear capability and defense posture second to none. More relevant, however, the Obama White House never pressured Britain or France to give up their independent nuclear deterrents. It looked to the world that the U.S. was fine with its allies having the bomb, but was worried that upstarts in North Korea, Iran, or Pakistan may cause trouble with their nuclear forces.

Although nuclear weapons are still around, it’s important to understand what has changed: the political and geostrategic context for their use.

Cold War nuclear crisis were two sided or bipolar affairs: the United States and the Soviet Union engaged in confrontations and conflicts over a variety of issues, dominated nuclear policy debates, and limited the nuclear aspirations of their allies and supporters.

Crises in the Second Nuclear Age of the twenty-first century will be different, and managing these crises will require new “apps” in conflict resolution and crisis management.

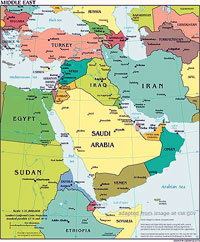

A major concern is the problem of risk management in regional “suction crises” that can develop in the Middle East, South or East Asia in a multipolar nuclear system. These suction crises have the potential to involve regional or global nuclear powers and to make the skill sets of risk management and escalation control more important than the ability to destroy targets promptly.

Either North Korea or Syria has the potential to be the first of these multilateral suction crises with a nuclear backdrop.

Either North Korea or Syria has the potential to be the first of these multilateral suction crises with a nuclear backdrop.

Nuclear weapons may be “used” in a future crisis without actually being fired. This is a Cold War lesson that carries over to the present time. They can back up diplomatic coercion, “madman” strategies, reassurance of allies and dissuasion of adversaries. In addition, the threat of “vertical” escalation can induce horizontal escalation outside the immediate theater of operations. For example, if the U.S. intensified its military activity in Syria, Russia could up the ante in Ukraine or in the Baltics at the same time. We can expect surprises, especially as the number of actors engaged expands. Some states or their supporting terrorist groups may think up an entirely new way of “using” nuclear weapons in brinkmanship tactics. We are possibly only at the start of a fifty year period of nuclear crises.

Few politicians or experts have thought through the implications of a regional nuclear crisis outside of Europe that expands to involve major powers and their nuclear arsenals. In such a crisis, the enlargement of the crisis may not take the form of a gradual, step-by-step expansion but instead be characterized by potboiling diplomacy, improvised military options and the risk of sudden, unexpected and unpredictable “explosions” into a wider and more dangerous confrontation. In addition, U.S. intelligence will be tasked to understand the mind sets of leaders whose decision rationalities are not like ours, and who are the products of states in decay and cultures in which zero-sum competition among armed factions of ethnic and religious fighters is the norm.

The problem is not that the U.S. does not have smart people to manage these things – we do. But bureaucracies are constellations of people embedded in institutional norms, expectations, cultures and standard operating procedures. Bureaucracies can only do successfully what they have rehearsed. So the first regional crises of the Second Nuclear Age may not even be recognized as such because these incidents could begin as low level counter-insurgencies or conventional wars involving only regional actors without nuclear arsenals – until the game changes. In such situations, we will be learning as we go.